WW2: DRESDEN 1945: Right to the VERY END, Germans were dishing out incredible beatings to the British RAF! – Schräge Musik & Scarecrow Shells!

Those German super-men were busy dishing out beatings to their enemies as overwhelmed as they were from all sides on land and in the air. The Germans were managing fight back in situations where any other nation would have given up long ago! The Germans are an incredible inspiration to all of us for the future, for saving our race!

I’ve mentioned the British lie that the Germans had invented “scarecrow shells”. You can read about it here: WW2: DRESDEN 1945: Britain lied to its bomber Pilots because they were so scared of the Germans! The Myth of Scarecrow Shells!! – http://dev.historyreviewed.best/index.php/2018/03/08/ww2-dresden-britain-lied-to-its-bomber-pilots-because-they-were-so-scared-of-the-germans-the-myth-of-scarecrow-shells/

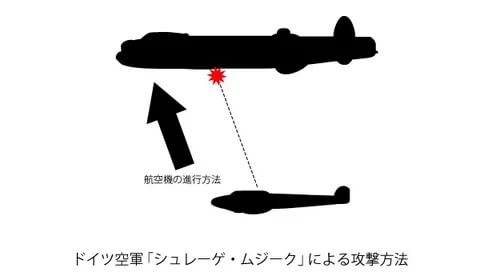

So the real weapon that may be responsible for entire bombers blowing up and falling apart were the German night fighters who were armed with a fascinating new invention! Schrage Musik was an upward firing cannon mounted on German night fighters. It allowed the plane to approach in the dark below and behind a bomber. It could then fire straight up into the unprotected underbelly of the plane. The only problem was that the German night fighter had to be really alert and agile because the bomber or parts of it could crash into the Germans! However, if they got their shots right they could blow up the entire plane by setting off the bombs inside – hence the “scarecrow shell”! See the diagrams below:

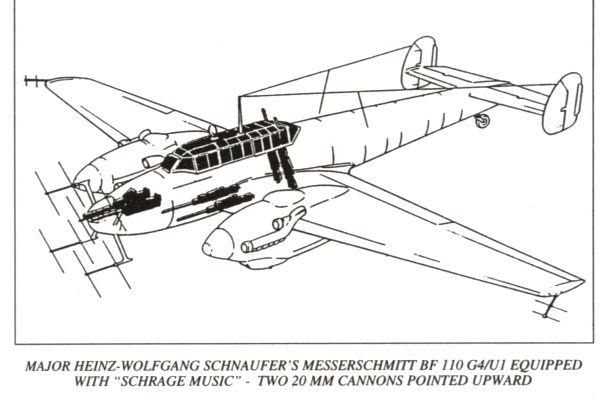

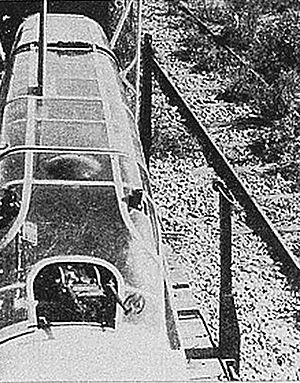

Below is a photo of a Schrage Musik gun – the tops of the guns are visible pointing directly upward on either side!

Captured Messerschmitt Bf 110G-4 fuselage showing the twin MG FF/M Schräge Musik installation, with the cannon muzzles just protruding from each side of the top of the rear cockpit, France c. 1944

This should give you an idea of just how close Hitler and the Germans came to WINNING in WW2, even right at the very end … even in 1945, just weeks and months before they surrendered! In the face of overwhelming odds, the Germans were still landing serious punches!

The massive British and American air fleets numbering hundreds or even thousands of huge bombers at a time (the likes of which the Germans did not have!), were unable to survive if their loss rate was higher than 10% per mission! In other words… even at that stage, Britain could be DEFEATED in the air!

But the massively outnumbered German super-men were coming close. They were not only scaring the British pilots and crews, but the high command knew that if the loss rate was too high, they would not be able to sustain the air war against Germany!

So keep in mind that tiny Germany, being invaded by 3 enormous global empires, was still dishing out serious beatings right into the final months of the war! That’s the key lesson that the rest of us whites must take away from this!

NB: When you read the actual tactics, it should be clear that this was extremely dangerous for the Germans, yet they were doing it regularly!

Here are excerpts from the full Schrage Musik article on wikipedia about this German weapon, and here you’ll see how well the Germans were adapting to these overwhelming events and still hurting and scaring their enemies right into the final months and even weeks of WW2!

From Wikipedia:

In World War II, Schräge Musik was the name Germans gave to upward-firing autocannon that the Luftwaffe mounted in night fighter aircraft. A similar fitment was used by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service and Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service and known by a different, undocumented name in their twin-engined night fighters. The Luftwaffe and the IJN air arm had their first victories with fighter-mounted upward-firing autocannons in May 1943.

Schräge Musik derives from the contemporary German colloquialism for shaky, off-tune music; literally, it translates to slanted or oblique music.

Night fighters used this device to approach and attack Allied bombers from below, outside the bomber crew’s usual field of view or fire. Most of the Allied bomber types of that era which were used for nocturnal bombing missions (primarily the Avro Lancaster) lacked effective ventral armament, leaving them easy prey to attacks from below, an advantage the Luftwaffe capitalized on.

An attack by a Schräge Musik-equipped fighter was typically a surprise to the bomber crew, who only realized a fighter was close by when they came under fire. Particularly in the initial stage of operational use, until early 1944, Allied crews often attributed sudden fire from below to ground fire rather than a fighter.[1]

Further down below Method of sighting guns we read:

What a contrast with SCHRÄGE MUSIK! Again the technique was to approach deliberately at a lower level, but this time all the night fighter pilot had to do was slow up a little, rise up below the bomber and hold formation. An NJG expert could follow his observer’s directions, acquire the bomber visually, close and destroy it within 60 seconds. The firing position, with the bomber 65° to 70° above the fighter, was an almost ideal one. The fighter could see the bomber clearly, as a darker silhouette either blotting out the stars or against paler sky or high cloud. It presented the biggest possible target and reflected any light from searchlights, ground fires or TIs [target indicators]. With the two aircraft in close formation, there was an ideal no-deflection shot. And the fighter was perfectly safe, because it was well below the Monica beam and could not be seen by any member of the bomber’s crew. The only snag was that the Luftwaffe’s guns were so effective that the night fighter usually had to get out of the way very fast. It was rather like 1916, except that a Lancaster with one wing blown off tumbled downwards and backwards faster than an ignited airship.[19] [N 2]

Note in the piece below, that Schrage Musik was working so well that for months the British were not even aware that German night fighters were busy destroying their bombers! Here it is:

Operational use

“We had dropped our bombs on a synthetic-oil plant in Gelsenkirchen, Germany the night of June 12/13, 1944 and were headed for base. In the tail gun turret I was searching in the dark for any enemy fighters who might be following us out of the target area. Suddenly I heard cannons barking loudly and saw lights flashing directly below. What the hell was that? I didn’t see the fighter – just the flashing. We took evasive action and that was it.

Air Gunner Leonard J. Isaacson.[20]

Schräge Musik (or Schrägwaffen, as it was also called) was first used operationally during Operation Hydra (the first instance of the Allied bombing of Peenemünde) on the night of 17/18 August 1943. [N 3] Three waves of aircraft bombed the area and a diversion on Berlin by RAF Mosquitoes, attracted the main Luftwaffe fighter effort and meant that only the last of the three waves was met by many night fighters.[21] Number 5 Group and RCAF 6 Group in the third wave, lost 29 of their 166 bombers, well over the 10 percent losses considered “unsustainable”.[citation needed] In this raid 40 aircraft were lost: 23 Lancasters, 15 Halifaxes and two Short Stirlings.

Adoption of Schräge Musik began in late 1943 and by 1944, a third of all German night fighters carried upward-firing guns. Schräge Musik proved most successful in the Jumo 213 powered Ju 88 G-6. An increasing number of these installations used the more powerful 30-millimetre (1.2 in) calibre, short-barrelled MK 108 cannon, such as those fitted to the Heinkel He 219, fully contained within the fuselage.[22] By mid-1944, He 219 aircrew were critical of the MK 108 installation, because its low muzzle velocity and limited range, meant that the night fighter had to be close to the bomber to attack and be vulnerable to damage from debris. They demanded that either the MK 108s be removed and replaced by MG FF/Ms or the angle of the mounting be changed. Although He 219s continued to be delivered with the twin 30 mm mounted, these were removed by front line units.[23] Using the Schräge Musik required precise timing and swift evasion; a fatally damaged bomber could fall on the night fighter, if the fighter could not quickly turn away. The He 219 was particularly prone to this; its high wing loading at the edge of stalling speed left it unmanoeuvrable.

Schräge Musik allowed German night fighters to attack undetected, using special ammunition with a faint glowing trail replacing the standard tracer, combined with a “lethal mixture of armour-piercing, explosive and incendiary ammunition.”[24] Approaching from below, provided the night fighter crew with the advantage that the bomber crew could not see them against the dark ground or sky, yet allowed the German crew to see the silhouette of the aircraft before they attacked. The optimum target for the night fighter was the wing fuel tanks, not the fuselage or bomb bay, because of the risk that exploding bombs would damage the attacker. “To overcome some of the problems, many NJG pilots closed the range at a lower level, below the Monica zone of coverage, until they could see the bomber above; then they pulled up into a climb with all front guns blazing. This demanded fine judgement, gave only a second or two of firing time and almost immediately brought the fighter up behind the bomber’s tail turret.

Schräge Musik produced devastating results, with its most successful deployment in the winter of 1943–1944. This was a time when Bomber Command losses became unsupportable: the RAF lost 78 of 823 bombers that attacked Leipzig on 19 February, and 96 of the 795 bombers that attacked Nuremberg on 30/31 March 1944. RAF Bomber Command was slow to react to the threat from Schräge Musik, with no reports from shot-down crews reporting the new tactic; the sudden increase in bomber losses had often been attributed to flak. Reports from air gunners, of German night fighters stalking their prey from below had appeared as early as 1943 but had been discounted. A myth developed among RAF Bomber Command crews that “scarecrow shells” were encountered over Germany. The phenomenon was thought to be “AA shells simulating an exploding four-engined bomber and designed to damage morale. In many cases these were actual ‘kills’ by Luftwaffe night fighters… It was not for many months that evidence of these deadly attacks was accepted.” [25]

A detailed analysis of the damage done to returning bombers, clearly showed that the night fighters were firing from below. Defence against the attacks included mixing de Havilland Mosquito night fighters into the bomber stream, to pick up radar emissions from the German night fighters.[19] Wing Commander J. D. Pattinson of 429 “Bison” Squadron, recognized an unseen danger but to him, it “was all presumption, not fact.” He ordered that the mid-upper turrets be removed and the “displaced gunner would lie on a mattress on the floor as an observer, looking through a perspex blister for night fighters coming up from below.”[14] While many Lancaster B. IIs had retained the FN64 ventral turret, a small number of Halifax and Lancaster bombers were unofficially fitted with a machine-gun, normally of .303 calibre but Canadian units tended to use the 0.50-inch (12.7mm) heavy machine gun. (If not installed in a ventral turret these weapons were mounted in a makeshift port directly under the mid-upper gunner station.)

Even in the last year of the war, 18 months after the Peenemunde Raid, Schräge Musik night fighters were still taking a fearful toll, for example on the Mitteland–Ems Canal Raid, 21 February 1945:

On this particular night the night fighters were to score heavily. The ground radar stations responsible for initial guidance to the vicinity of the bombers did their job well, as did the airborne radar operators to whom fell the task of final location of individual targets. The path of the returning bomber stream was clearly marked by the pyres of numerous downed victims. NJG 4 was operating from Gutersloh (later an RAF base) and in the space of 20 minutes, between 20.43 and 21.03, Schnaufer and his crew, using their upward firing cannons [from a Bf 110G night fighter], shot down seven Lancasters. As it was, on that black night, four night fighter crews accounted for 28 of the 62 bombers lost out of the 800 despatched.[26]

So in the above you can see that a mere 4 night fighters with their German super-men shot down 28 bombers in 20 minutes in February 1945! This is a few days after the firebombing of Dresden and the Germans were still kicking ass! The British came close to almost hitting their 10% loss rate which for them was unsustainable!

Those German super-men were rocking! 14/88. Jan