Video: WW2: Schnellboot: The Last German E-Boat – History of the amazing E-Boats

[This is a fascinating story. What I particularly enjoyed was the way these little E-Boats were the only German weapons to attack the D-Day invasion forces in Britain, and they left something like 749 dead!!! An astounding feat. It was so embarrassing that the allies covered the whole thing up and never told people about this amazing German feat on British shores!!

The record of these German torpedo boats in WW2 is astounding! Jan]

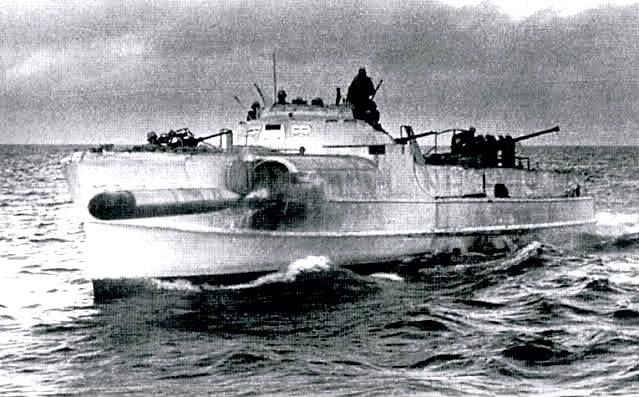

S-130 is the very last of Germany’s sleek S-Boats, the fast motor torpedo boats known to the British as E-boats, that ravaged shipping around the shores of the UK. Now being restored in Britain, this boat is a rare wartime survivor with an equally fascinating postwar story to match.

Here is an account of how these nifty little E-Boats dared to take on the massive Allied might of D-Day:-

In 1928, after many tests in the North Atlantic, German Naval Command settled on a rounded-bottom hull. They chose the hull of the “Oheka II”, a luxury motor yacht built in 1927 by the German boatyard Luerssen. The hull measured 73 feet, 8 inches (22.5 meters) long and displaced 22.5 tons with a top speed of 34 knots making her the world’s fastest boat of her class of the day. During sea trials, the boat ploughed through the water with plume as required, even when all three of her Maybach 550 horsepower engines were used. The rounded hull was made of wood planking to help reduce the weight and flattened at the stern area so the aft section area in water at high speeds was reduced, allowing more hydrodynamic lift when keeping the craft on a horizontal plane. In November of 1929, the German shipbuilder Luerssen was given a contract to build a boat to the new military-quality design. Two torpedo tubes were added along the forward castle and the engines upgraded for increased speed. It would become the first Kriegsmarine’s standardized “Schnellboot” (“Fast Boat”) and know in its abbreviated form as the “S-Boot” with the designation of “S-1”. With improvements from the field filtered back to Luerssen, the basic design formed all future S-Boots built during World War 2 (1939-1945).

As the first S-Boots – eventually known to the Allies as “E-Boats” – were produced, additional improvements were being designed almost boat-to-boat. The second boat, S-2, was built with an advanced rudder assembly intended to reduce stern waves. This upgrade would help keep the boat in a horizontal attitude that increased the stability of the three propellers. In 1933, the boats produced needed to reserve the bow buoyancy so, starting with the construction of S-7, the hull as adjusted, preventing the boat from nosing deep into oncoming bow waves consistent with North Atlantic heavy weather. During the construction of S-20, the boat’s superstructure was constructed so the boat’s commander could stand on deck behind a wind and spray screen. This made communication difficult, requiring the commander to issue orders through a voice tube or by a seaman equipped with a headset intercom relaying information to the helmsman, navigator, and radio operator housed behind him in the wheel-house.

By 1940, when S-26 was constructed, a cockpit was added into the wheelhouse roof area. This addition allowed some shelter for the commander against the elements and increased visibility from a perched central location on the boat. An advantage of this change allowed the commander to speak orders directly to the crew in the wheelhouse without voice tubes. Starting with S-30 in 1939, several boats were built with a slightly smaller hull at 32.7 meters long and with the old style wheelhouses. By the time S-38 and her batch class was built, including S-130, an armored bridge had been added as well as additional anti-aircraft defensive armament: 2 x 20mm AA guns amidships plus 1 x 37mm AA gun mounted aft. In 1943, all S-Boots were reclassified as the “S-110” class.

On October 21st, 1943, the Johann Schlichting facility at Travemuende, Germany near Kiel, built S-130 (Hull No. 1030), codenamed “Rabe”. She had incorporated all of the upgrades that had been tested and proved in-the-field to date. In November, S-130 was assigned to the 9th S-Boot Flotilla to help strengthen the German presence in the English Channel and North Atlantic. The 9th S-Boot Flotilla was stationed in Rotterdam from November 1943 until early 1944 to which the flotilla was then moved to Cherbourg situated on the Cotentin peninsula at Lower Normandy in northwest France. The flotilla’s primary mission was to patrol the Channel and the North Atlantic and torpedo Allied shipping, depth charge submarines, lay mine fields and provide costal patrol duties.

Operating out of the port of Rotterdam, Cherbourg, S-130 would patrol looking for targets of opportunity while also being posted to convoy duty and general patrol. For the first six months, her patrol missions were routine without enemy action to be had. On the afternoon of April 27th, 1944, a Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft spotted an Allied convoy of seven merchant ships off Start Point, England. The 5th and 9th S-Boot flotillas were radioed and nine S-Boots (including S-130) were dispatched from Cherbourg at 10PM to attack the convoy. The S-Boots were actually alerted to a convoy on a training exercise codenamed “Tiger” – practicing for the forthcoming Normandy D-Day invasion.

The United States Army was conducting assault force landing training exercises at Slapton Sands in Start Bay and nearby Tor Bay to condition troops before attacking Normandy, France. The training was realistic, utilizing ships that would be operating during the invasion to provide the most realistic experience as possible. Convoy T-4 consisted of the British corvette HMS Azaelia, assigned as the escort for the exercise, and a number of minesweepers preceding eight Landing Ship Tank (LST) vessels as they entered Lyme Bay.

LSTs were massive vessels displacing 5,410 long tons (5,497 short tons) when fully-loaded and were 400 feet (120 meters) in length. Each ship could hold thirteen Churchill Infantry Tanks or twenty medium-class tanks below deck and twenty-seven vehicles of various sizes on the upper deck. Additionally, each ship could house 193 combat-ready personnel plus gear. To operate the LST required a crew of 169 officers and seamen – operation including the loading and offloading of cargo onto an enemy beach. The LST was designed to beach itself to which then the bow split open to allow tanks and vehicles to drive down a ramp onto the beach. As the 13 to 20 tanks are driven out of the lower tank deck, a second ramp allowed vehicles to be driven directly from the main deck down to the lower tank deck, ultimately crossing the bow ramp onto the beach – this intended to decrease overall disembark time.

As the training LSTs slowly steamed towards the beach, S-130 and the other German S-Boots were incoming at 36 knots, entering Lyme Bay while sighting the allied ships. They proceeded into attack formation and engaged at 2AM. The 9th Flotilla of S-130, S-145 and S-150 were closing at maximum speed and S-150 and S-130 turned straight in to a joint torpedo attack against one vessel. S-145 broke off to attack a landing craft. S-140 and S-142 identified targets at about the same time and opened fire with four torpedoes at 1,400 meters away. Meanwhile, S-100 and S-143, alerted to the action by red tracers to their north, closed in at high speed and noted that a “tanker” was already well ablaze. Both boats fired two torpedoes at a ship, probably one of the mine sweepers, achieving a solid hit with one torpedo.

The first LST torpedoed was LST-507 which showcased explosions and fires as fuel ignited. Next hit was LST-531 targeted by two torpedoes and quickly sunk by the head. LST-289 was torpedoed 28 minutes later but remained afloat, losing 13 men in the action. LST-507 lost 202 men with the remainder making it to life boats. LST-531 had sunk almost immediately after being torpedoed, not allowing many of the crew and army troops to escape – 424 men lost. During the night battle, LST 496 was firing at an S-Boot and racked LST-511 with machine gun fire, wounding 18 crewmen. In the end, a total of 684 American seamen and soldiers were killed or went missing after the short successful German attack. The action worried Allied D-Day planners so the facts of the mission were not released to the public or relatives of the men lost. The KIA’s numbers were added to the losses incurred by the Allies on D Day itself.

On the morning of 6th, June 1944, D-Day, the allied invasion of “Fortress Europe” (codenamed Operation Neptune) began. The Allied invasion fleet included ships from eight different navies, comprising 6,939 vessels. 1,213 were warships including 7 battlewagons, 5 heavy and 17 light cruisers, 135 destroyers and destroyer escorts and 508 other monitor-like warships, “E-boats” and motor gunboats. The balance was 4,126 landing ships such as the LST type and other landing craft, including 736 ancillary craft made up of tug boats and 864 support merchant vessels. The first German naval response came from the S-Boot 9th Flotilla through S-130 and 30 other S-Boots sent in to attack the invading Allied fleet. The maximum combined fire power of the 31 boats was 124 torpedoes.

As the S-Boots approached the invasion fleet, it became apparent to the Kriegsmarine 9th Flotilla commander attacking this wall of steel was a suicide mission as the S-Boots were not designed to stand and fight destroyers and cruisers. The order was to launch all torpedoes towards the oncoming ships at their maximum range and return home. Some landing craft were sunk during this engagement and two of S-130’s crew were killed but, due to the range that the torpedoes were launched, the individual S-Boots could not claim credit for warships sunk. The 9th Flotilla sank a number of landing craft but records do not indicate whether any were attributed to S-130. During the next 11 months, as the Allied armies advanced towards the Rhine River and Germany itself, S-130 and the 9th Flotilla fell back in the Channel and along the North Sea coasts, disrupting Allied lines of communication and attacking shipping whenever they could. The advances of the allies by the spring of 1945 had halted German Naval operations in the southern North Sea altogether.

Source: https://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail.asp?ship_id=Schnellboot-SBoot

Here’s a more comprehensive history of the kick-ass E-Boats:-

E-boat was the Western Allies‘ designation for the fast attack craft (German: Schnellboot, or S-Boot, meaning “fast boat”) of the Kriegsmarine during World War II. The most popular, the S-100 class, were very seaworthy,[1] heavily armed and capable of sustaining 43.5 knots (80.6 km/h; 50.1 mph), briefly accelerating to 48 knots (89 km/h; 55 mph).[2]

These craft were 35 metres (114′ 10″) long and 5.1 metres (16′ 9″‘) in beam.[3] Their diesel engine propulsion had substantially longer range (approximately 700 nautical miles) than the gasoline-fueled American PT boat and the generally similar British Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB).

As a result, the Royal Navy later developed better-matched versions of MTBs using the Fairmile ‘D’ hull design.

Development

This design was chosen because the theatre of operations of such boats was expected to be the North Sea, English Channel and the Western Approaches. The requirement for good performance in rough seas dictated the use of a round-bottomed displacement hull rather than the flat-bottomed planing hull that was more usual for small, high-speed boats. The shipbuilding company Lürssen overcame many of the disadvantages of such a hull and, with the Oheka II, produced a craft that was fast, strong and seaworthy. This attracted the interest of the Reichsmarine, which in 1929 ordered a similar boat but fitted with two torpedo tubes. This became the S-1, and was the basis for all subsequent E-boats.[citation needed]

After experimenting with the S-1, the Germans made several improvements to the design. Small rudders added on either side of the main rudder could be angled outboard to 30 degrees, creating at high speed what is known as the Lürssen Effect.[4] This drew in an “air pocket slightly behind the three propellers, increasing their efficiency, reducing the stern wave and keeping the boat at a nearly horizontal attitude”.[5] This was an important innovation as the horizontal attitude lifted the stern, allowing even greater speed, and the reduced stern wave made E-boats harder to see, especially at night.[citation needed]

Operations with the Kriegsmarine

E-boats, a British designation using the letter E for Enemy,[6][7] were primarily used to patrol the Baltic Sea and the English Channel in order to intercept shipping heading for the English ports in the south and east. As such, they were up against Royal Navy and Commonwealth, e.g., Royal Canadian Navy contingents leading up to D-Day, Motor Gun Boats (MGBs), Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs), Motor Launches, frigates and destroyers. They were also transferred in small numbers to the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea by river and land transport. Some small E-boats were built as boats for carrying by auxiliary cruisers.

Crew members could earn an award particular to their work—Das Schnellbootkriegsabzeichen—denoted by a badge depicting an E-boat passing through a wreath. The criteria were good conduct, distinction in action, and participating in at least twelve enemy actions. It was also awarded for particularly successful missions, displays of leadership or being killed in action. It could be awarded under special circumstances, such as when another decoration was not suitable.

E-boats of the 9th flotilla were the first naval units to respond to the invasion fleet of Operation Overlord.[8] They left Cherbourg harbour at 5 a.m. on 6 June 1944.[8] On finding themselves confronted by the entire invasion fleet, they fired their torpedoes at maximum range and returned to Cherbourg.[8]

During World War II, E-boats claimed 101 merchant ships totalling 214,728 tons.[9] and 12 destroyers, 11 minesweepers, eight landing ships, six MTBs, a torpedo boat, a minelayer, a submarine and a number of smaller craft, such as fishing boats. They also damaged two cruisers, five destroyers, three landing ships, a repair ship, a naval tug and numerous other merchant vessels. Sea mines laid by the E-boats were responsible for the loss of 37 merchant ships totalling 148,535 tons, a destroyer, two minesweepers and four landing ships.[9]

In recognition of their service, the members of E-boat crews were awarded 23 Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and 112 German Cross in Gold.[9]

Italian MS boat

The poor seaworthiness of the Italian-designed MAS boats of World War I and early World War II led its navy to build its own version of E-boats, the CRDA 60 t type, classed MS (Motosilurante). The prototype was designed on the pattern of six German-built E-boats captured from the Yugoslav Navy in 1941. Two of them sank the British light cruiser HMS Manchester in August 1942, the largest victory by fast torpedo craft in the Second World War.[17] After the war these boats served with the Italian Navy, some well into the 1970s.[18]

The Kriegsmarine supplied the Spanish Navy with six E-boats during the Spanish Civil War, and six more during the Second World War. Another six were built in Spain with some assistance from Lürssen. One of the early series, either the Falange or the Requeté, laid two mines during the civil war that crippled the British destroyer HMS Hunter off Almería on 13 May 1937. The German-built boats were discarded in the 1960s, while some of the Spanish-built ones served until the early 1970s.[19]