USA: When Blacks massacred Whites: The Wichita Massacre

Stephen Webster, American Renaissance, August 2002

The Carr brothers.

On September 9, Reginald Carr and his brother Jonathan go on trial for what has become known as the Wichita Massacre. The two black men are accused of a weeklong crime spree that culminated in the quadruple homicide of four young whites in a snowy soccer field in Wichita, Kansas. In all, the Carr brothers robbed, raped or murdered seven people. They face 58 counts each, ranging from first-degree murder, rape, and robbery to animal cruelty. Prosecutors will seek the death penalty.

The only survivor of the massacre is a woman whose identity has been protected, and who is known as H.G. In statements to police and in testimony at an April 2001 preliminary hearing, the 25-year-old school teacher offered horrible details of what happened on the night of Dec. 14, 2000. That evening, a Thursday, H.G. went to spend the night at the home of her boyfriend, Jason Befort. Mr. Befort, 26, a science teacher and coach at Augusta High School, lived in a triplex condo with two college friends: Bradley Heyka, 27, a financial analyst, and Aaron Sander, 29, who had recently decided to study for the priesthood.

When H.G. arrived with her pet schnauzer Nikki around 8:30 p.m., her boyfriend Mr. Befort was not there, but the two roommates were. A short time later, Mr. Sander’s former girlfriend, Heather Muller, a 25-year-old graduate student at Wichita State University who worked as a church preschool teacher, joined them. At about 9 p.m., H.G. went to her boyfriend’s ground-floor bedroom to grade papers and watch television. Mr. Befort came home from coaching a basketball practice around 9:15, and at 10:00, H.G. decided to go to bed. Before joining H.G in bed, Mr. Befort made sure all the lights in the house were turned off and all the doors were locked. Mr. Sander was sleeping on a couch in the living room while his former girlfriend slept in the second ground-floor bedroom. Mr. Heyka slept in a room in the basement.

Shortly after 11 p.m., the porch light came back on, to the surprise of Mr. Befort, who was still awake. H.G. says that seconds later she heard voices, then shouting. Her boyfriend cried out in surprise as someone forced open the door to the bedroom. H.G saw “a tall black male standing in the doorway.” She didn’t know how the man got into the house, and police investigators have not said how they think the Carrs got in. She says the man, whom she later identified as Jonathan Carr, ripped the covers off the bed. Soon, another black man brought Aaron Sander in from the living room at gunpoint and threw him onto the bed. H.G. saw that both men were armed. She said they wanted to know who else was in house, and the terrified whites told them about Mr. Heyka in the basement and Miss Muller in the other ground-floor bedroom. The intruders brought them into Mr. Befort’s bedroom.

“We were told to take off all of our clothes,” says H.G. in her testimony. “They asked if we had any money. We said: ‘Take our money . . . Take whatever you want.’ We didn’t have any (money).”

The Carrs, however, were not at that point interested in money. They made the victims get into a bedroom closet, and for the next hour brought them out to a hall by a wet bar, singly or in pairs for sex. In the closet-perhaps 12 feet away from the wet-bar area-the victims were under orders not to talk. H.G. says that when the Carrs heard whispering they would wave their guns and shout “Shut the fuck up.”

The Carrs first brought out the two women, H.G and Heather Muller, and made them have oral sex and penetrate each other digitally. They then forced Mr. Heyka to have intercourse with H.G. Then they made Mr. Befort have intercourse with H.G, but ordered him to stop when they realized he was her boyfriend. Next, they ordered Mr. Sander to have intercourse with H.G. When the divinity student refused, they hit him on the back of the head with a pistol butt. They sent H.G. back to the bedroom closet and brought out Miss Muller, Mr. Sander’s old girlfriend. H.G. testified she could hear what was going on out by the wet bar, and when Mr. Sander was unable to get an erection one of the Carrs beat him with a golf club. Then, she says, the Carr brothers “told [Aaron] that he had until 11:54 to get hard and they counted down from 11:52 to 11:53 to 11:54.” The deadline appears to have brought no further punishment, and Mr. Sanders was returned to the closet. The Carrs then forced Mr. Befort to have intercourse with Heather Muller, and then ordered Mr. Heyka to have sex with her. H.G. says she could hear Miss Muller moaning with pain.

The Carrs asked if the victims had ATM cards. Reginald Carr then took the victims one at a time to ATM machines in Mr. Befort’s pickup truck, starting with Mr. Heyka. While Reginald Carr was away with Mr. Heyka, Jonathan Carr brought H.G. out of the closet to the wet bar, raped her, and sent her back to the closet. Reginald Carr returned with Mr. Heyka, and ordered Mr. Befort to go with him. Mr. Heyka was put back in the closet but said nothing about his trip to the ATM machine. Mr. Sander asked Mr. Heyka if they should try to resist, assuming they would be killed anyway, but Mr. Heyka did not reply. While Reginald Carr was away with Mr. Befort at the cash machine, Jonathan Carr ordered Heather Muller out of the closet and raped her.

When Reginald Carr returned with Mr. Befort, H.G. volunteered to go next. Mr. Carr let her put on a sweater, but nothing else, and said he liked seeing her with no underwear. He ordered her to drive the truck to a bank, and told her not to look at him as he crouched in the back seat. “I asked him if he was going to hurt us and he said, ‘No,’” she says. “I said, ‘Do you promise you’re not going to kill us?’ and he said, ‘Yes.’”

H.G. got money from the cash machine and adds, “On the way back, he said he wished we could’ve met under different circumstances. He said I was cute, and we probably would’ve hit it off.” When the two got back to the house, Reginald Carr raped H.G. and ejaculated in her mouth. Jonathan Carr raped Miss Muller again, and then he raped H.G. one more time. Afterwards, the intruders ransacked the house looking for money. They found a coffee can containing an engagement ring Jason Befort had bought for his girlfriend. “That’s for you,” he told H.G., “I was going to ask you to marry me.” That is how H.G. learned her boyfriend planned to propose to her the following Friday, Dec. 22.

At one point, says H.G., Reginald Carr “said something that scared me. He said ‘Relax. I’m not going to kill you yet.’”

The Final Ride

The Carrs led the victims outside into the freezing night. At midnight it had been 17.6 degrees, and there was snow on the ground. The Carrs let the women wear a sweater or sweatshirt, but they were barefoot, and naked from the waist down. The men were marched into the snow completely naked. The Carrs tried to force all the victims into the trunk of Aaron Sander’s Honda Accord, but realized five people would not fit, and made only the men get into the trunk. Reginald Carr ordered H.G. to join him in Mr. Befort’s truck, and Jonathan Carr drove the Accord with the three men in the trunk and Miss Muller inside. As Mr. Carr drove her off, H.G. noted the time: It was 2:07 a.m., three hours since the ordeal began.

After a short drive, both vehicles stopped in an empty field. Reginald Carr ordered H.G. to go sit with Miss Muller in Mr. Sander’s car. A moment later, she saw the men line up in front of the Honda. In her testimony H.G. said, “I turned to Heather and said, ‘They’re going to shoot us.’”

The Carr brothers ordered H.G. and Miss Muller out of the car. Miss Muller stood next to Mr. Sander, her former boyfriend, while H.G. stood beside her boyfriend, Mr. Befort. The Carrs ordered them to turn away and kneel in the snow. “As I was kneeling, a gun shot went off,” says H.G. “[Then] I heard Aaron [Sander] . . . I could distinguish Aaron’s voice. He said, ‘Please, no sir, please.’ The gun went off.”

H.G. heard three shots before she was hit: “I felt the bullet hit the back of my head. It went kind of gray with white like stars. I wasn’t knocked unconscious. I didn’t fall forward. Then someone kicked me, and I had fallen forward. I was playing dead. I didn’t move. I didn’t want them to shoot me again.”

As H.G. lay in the snow, the Carrs drove off in Jason Befort’s pickup, running over the victims as they left. H.G. says she felt the truck hit her body, too.

“I waited until I couldn’t hear any more,” she says. “Then I turned my head and saw lights going. I looked at everyone. Everyone was face down. Jason [Befort] was next to me. I rolled him over. There was blood squirting everywhere, so I took my sweater off and tied it around his head to try and stop it. He had blood coming out of his eyes.”

In the distance, H.G. saw Christmas lights. Barefoot and naked, with a bullet wound in the head, she managed to walk more than a mile in the freezing cold, through snow, across a field and construction site, around a pond, and through the brush, until she reached the house with the lights. She pounded frantically on the door and rang the doorbell until the young married couple who lived there woke up. “Help me, help me, help me,” she pleaded. “We’ve all been shot. Three of my friends are dead.” (At the time, H.G. thought her boyfriend was still alive.)

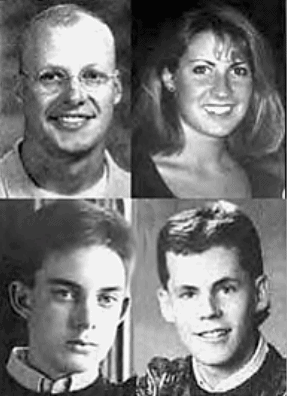

Four of the victims. Clockwise from top left:

Jason Befort, Heather Muller, Aaron Sander,

Bradley Heyka.

The couple wrapped H.G. in blankets, and reached for the phone to dial 911, but she would not let them call. She was afraid she would die, and wanted to tell what had happened. She described the attackers and what they did, as the couple listened in amazement at her courage and determination. Only when she was sure they knew her story did she let them call the police. Still thinking she would die, she asked them to call her mother-”Tell her I love her”-and her boyfriend’s parents. She was worried about the children she teaches, and kept wondering “Who’s going to take care of the kids in school?”

When the police arrived they questioned H.G. briefly before paramedics took her to the hospital. From her description of Mr. Befort’s truck, they were able to get the license plate number from the vehicle’s registration records, and put out an alert. As dawn broke, radio and television stations were broadcasting the plate number.

H.G. did not know that after the Carrs shot her friends they drove back to the triplex and loaded Mr. Befort’s truck with everything of value they could find. They also committed their final killing. The police found H.G.’s pet schnauzer Nikki lying in a pool of blood on a bed, probably shot.

By 7:30 a.m., police had a report that the missing truck was outside a downtown apartment building, and that a black man had been carrying a television set up to one of the apartments. The police moved in to seal off the area. Two officers knocked on the door of the apartment, and after several minutes a white woman named Stephanie Donly opened the door. She was Reginald Carr’s girlfriend, and shared her apartment with him. Police caught Mr. Carr as he tried to slip out a window.

The police learned from Miss Donly that Reginald’s brother Jonathan was driving a late model Plymouth Fury. Shortly after 12:00 p.m. they found the car parked outside a house in a black part of town. Jonathan Carr was there with his girlfriend of a few days, Tronda Green. He bolted when he saw the police, but was caught after a short chase. Fewer than 12 hours after the murders, Reginald and Jonathan Carr were both in custody.

Other Victims

That night’s quadruple murder was only the most gruesome of a series of Carr brother attacks. Late on the night of Dec. 7, 2000-just one week earlier-Andrew Schreiber, a 23-year-old white man, stopped at a Kum and Go convenience store in East Wichita. Reginald and Jonathan Carr forced themselves into his car at gunpoint and made Mr. Schreiber drive to various ATM machines and withdraw money. “I was just hoping if I did what they said, they’d let me live,” he says. The two split up, and one followed in another car as they made him drive to a field northeast of town. There they pistol-whipped him, dumped him out of the car, and fled in the other vehicle after shooting out Mr. Schreiber’s tires.

Four days later, the Carrs tried to hijack 55-year-old Linda Walenta’s SUV while she sat in it in the driveway of her suburban East Wichita home. The Carrs were looking for an SUV in which to drive people at gunpoint to ATMs. They thought they could keep their victims out of sight in a large vehicle as they drove through town. One of the brothers approached Mrs. Walenta, apparently asking for help of some kind. She was suspicious because she thought a car had been following her, and rolled her window down just a little to hear what he was saying. He stuck a gun sideways into the opening, and shot her several times as she tried to drive away. Mrs. Walenta, a cellist in the Wichita Symphony Orchestra, survived the shooting but was paralyzed from the waist down. She was able to help police in their investigation, but died of her wounds three weeks later, on January 2, 2001.

Linda Walenta

Wichita police confirmed the Carr link to all the crimes when a highway worker found a black .380 caliber Lorcin semi-automatic handgun along Route 96, a highway near the soccer field where the massacre took place. The Kansas state crime lab confirmed that it was the weapon used to kill Mrs. Walenta and H.G.’s friends, and to shoot out the tires of Andrew Schreiber’s car. No one knows what other crimes the brothers may have committed, but they certainly appeared guilty of these.

The Carr trial is scheduled to start on Sept. 9, but has been delayed by defense maneuvering. On June 13, Judge Paul Clark denied a motion to move the trial out of Sedgwick County. The defense cited a poll showing 74 percent of Sedgwick County residents thought the Carrs were either “definitely guilty” or “probably guilty,” and argued the brothers could not get a fair trial in Wichita. However, no trial has been moved from Sedgwick County in more than 40 years, and this one will stay.

The defense wanted separate trials because the lawyers for each brother will try to blame the crimes on the other. The lawyers argued they will both be trying to help convict the other brother, so it will be like having two prosecutors for each defendant. Prosecutor Nola Foulston pointed out that many people accused of committing crimes together are tried together, and since the trial is expected to last a month and involve 70 witnesses, two trials would be too much expense and inconvenience.

Jonathan Carr’s lawyers also tried to get him declared unfit to stand trial, but on April 8, 2002, Judge Clark reviewed the reports of two mental health experts, and ruled him competent. The reports are under seal, so the grounds for the motion are not known.

If the Carr brothers’ lawyers do try to blame each other’s client, the jury will learn that both have long criminal records. Jonathan Carr’s appears to be under seal but at least parts of his brother’s are public. In 1995, Reginald Carr was sentenced to 13 months in prison for theft. He was also ordered to serve six months each for aggravated assault and subverting the legal process. In 1996, he was sentenced to 28 months on a drug charge. He was paroled on March 28, 2000, but that November was booked for drunk driving. A few days later he was back before a judge, charged with forgery and parole violation. Police mistakenly let him out six months early on Dec. 5, 2000, just two days before he robbed and beat Andrew Schreiber, and started his week of crime. Had police followed correct procedures Jason Befort, Bradley Heyka, Aaron Sander, Heather Muller and Ann Walenta would probably still be alive.

“Has No Bearing”

Although the perpetrators are black and all their victims white, the Wichita police have dismissed race as a motive. Prosecutor Foulston says the Carr brothers chose their victims at random, not because they were white, and that the motive was robbery. “It reasonably appears that these were isolated incidents where individuals . . . were chosen at random . . . a random act of violence,” she says. “The fact that the defendants and victims happen to be of different races has no bearing. Let’s just look at the underlying crimes.” The Wichita media consistently downplayed the racial angle.

However, as news of the crimes spread across the Internet, many people began to wonder if the Carrs would be charged with hate crimes. In fact, it does not appear that Mrs. Foulston or police investigators even looked for a possible racial motive. According to the testimony of the April 2001 preliminary hearing, in which prosecutors determined whether they had enough evidence to support charges, Mrs. Foulston never asked H.G. or Andrew Schreiber if the brothers used racial slurs, or expressed hatred of whites.

It is true that Reginald Carr had a white girlfriend, and it may be that the race of the victims was unimportant to him. At the same time, Jonathan Carr wore a FUBU sweatshirt, a brand popular with black rappers that is said to stand for “For Us, By Us.” Some blacks wear FUBU clothing as a statement of black solidarity if not outright rejection of whites.

Louis Calabro of the European American Issues Forum (EAIF) and a former San Francisco police lieutenant, has written to Mrs. Foulston describing the FBI’s guidelines for suspecting a hate crime when perpetrator and victim are of different races. Among them are excessive violence, a pattern of similar attacks, and the cold-bloodedness of an execution-style killing. Combined with the torture of forcing people naked into a freezing night, and the degradation the Carrs put their victims through, there is ample reason at least to suspect a racial motivation.

Of one thing we can be certain: If whites had done something this horrible to blacks, it would be universally assumed the crime was motivated by racial hatred. From the outset, police and prosecutors would have investigated the friends, habits, reading matter, and life history of each defendant. If either had ever uttered the word “nigger,” had a drink with a Klansman, or owned a copy of American Renaissance, this would be discovered and brandished as proof of racial hatred. In the Carr case, there appears to have been no investigation at all. Instead of searching for possible racial animus, the authorities have simply declared there was none.

Mrs. Foulston dodges the racial question by pointing out that Kansas does not have a hate crime statute, but the state does specify harsher penalties for bias crimes. Given that the Carr brothers face the death penalty, this is a moot point, but Mrs. Foulston has made no attempt to apply these provisions.

Mrs. Foulston knows some whites are pushing for a hate crimes investigation, and wants to keep the proceedings secret. She moved to close the court for the preliminary hearings, saying “we’d have to let the Aryan Nations come in here if they decided they had an interest.” At one hearing, reporters heard one of Mrs. Foulston’s aides tell the judge that the press are “interlopers,” and the public has no “substantial interest” in the case. Fortunately, Judge Clark recognizes the public’s right to observe the proceedings, and opened them to the public. He did, however, agree to Mrs. Foulston’s motion for a gag order on all lawyers, investigators and witnesses. The order also prevents release of many records that normally would be public, including the EMS records, the reports on Jonathan Carr’s mental competence, and records of police interviews. Mrs. Foulston says secrecy is necessary to ensure the Carrs get a fair trial, but what is in notes of police interviews, for example, that is so inflammatory it could prejudice the public? Evidence of racial hatred, perhaps?

Mrs. Foulston did not ask for a gag order in the case of another quadruple homicide in Wichita just eight days before the Carr brothers’ massacre. The DA’s office says that case, in which murderers and victims were black, did not generate nearly as many requests for public records, but in an open society, the more interest the public shows in information the more available it should be. Mrs. Foulston’s secrecy has led critics to accuse her of covering up evidence of racial animus. EAIF’s Mr. Calabro believes the assaults and murders “were racially motivated crimes that the DA and city of Wichita have no interest in pursuing.” Del Riley, a white Wichita resident who has followed the case, says of his reaction to the DA’s secrecy, “I wouldn’t call it outrage, but I’d call it suspicion. This gag order upsets me.”

Once again, we can be certain that if the racial cast of characters were reversed, there would be no attempt to close the court, and the media coverage-virtually absent in this case-would be deafening. A white-on-black crime of this kind would be front-page news for days, and would probably prompt official condemnation from the President and Attorney General on down. As we know from the reaction to the murder of James Byrd, dragged to death behind a truck, a crime of this sort committed by whites against blacks would put the nation into an official state of near hysteria.

What if the cast had been all-white? It would still have been national news. In 1959, drifters Dick Hickock and Perry Smith murdered the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas. Like the Wichita case, it was a home invasion, apparently motivated by robbery. Even without spectacular sexual cruelty, the Clutter killings were front-page news and the story was immortalized in Truman Capote’s novel, In Cold Blood. Had the Wichita case involved whites only, the heroics of H.G. alone would have ensured wide coverage. She would have become a national hero, part of the folklore of strong womanhood.

What if perpetrators and victims had all been black? Some in the media would have promoted the heroism of the woman who lived to tell of the crime, but others would have stayed away from the story because such savagery reflects badly on blacks.

When blacks commit outrages against whites, media executives not only downplay black misbehavior but believe they must protect whites from “negative stereotypes” about blacks. If they must report such crimes, they are likely to link them to editorials calling for tolerance, and pointing out that the criminals were individuals, not a race. When whites commit outrages against blacks there are no such cautions; white society at large is to blame.

The Carr brothers’ crimes were treated to a virtual media blackout. The Chicago Tribune and the Washington Times appear to be the only major non-Kansas dailies ever to mention the story. Their articles briefly described the facts of the case, and then focused on Internet discussions among whites who thought the Carr brothers were hate criminals. The Associated Press ran stories on the crimes, but they do not appear to have been picked up outside of Kansas. Within the state, the media dutifully promoted Mrs. Foulston’s categorization of the crimes as “random.” The networks, of course, were silent.

Were it not for the Internet, the Wichita story would have disappeared. It was only in chat-rooms and on web pages that the crimes had a national audience. Several sites, such as www. NewNation.org and www.JeffsArchive. com, have posted newspaper articles about the crimes. The main paper that covered the case, the Wichita Eagle, stores older articles in a fee-charging archive, so these sites are virtually the only way the public can learn about the massacre.

It will be surprising if the trial itself gets national coverage. Kansas permits television in courtrooms, but so far, the Court TV cable channel shows little interest in the case despite e-mail requests to its website at www.CourtTV.com. The Wichita Eagle will probably offer restrained coverage.

The police and media reactions to these crimes-a refusal to think about race, draw larger conclusions, or even express outrage-are typical of today’s whites, and in stark contrast to the sustained fury we could expect from blacks if the races were reversed.

Not even the acknowledged error that resulted in Reginald Carr’s early release seems to upset many people. Bradley Heyka’s father is angry, saying he is “appalled a mistake like this could lead to such severe consequences for so many people,” but Aaron Sander’s father is passive. “It is unfortunate this happened, but we have to learn to get past that and let those things go and get on with our life,” he says. “We can’t deal with how things should have been or could have been, we can only deal with today.”

There were even more cloying sentiments at the funerals of the young victims. At Jason Befort’s service on Dec. 21, 2000, Rev. James Diecker told the congregation their attitude towards the killers should be that of Jesus on the cross, when he said “Forgive them, Father, for they know not what they do.” He went on to call for “a victory of love over hate . . . a victory of mercy over justice.”

At Heather Muller’s funeral, Rev. Matthew McGinness struck the same note, saying, “We must be like Christ, who forgave his enemies.” He told the congregation Heather’s mother felt the same way, and had told him, “Heather would want us to pray for her murderers, and Heather was probably praying for them at the moment of her death.”

To what extent does this turn-the-other-cheek mentality explain why five whites failed to fight back against two attackers? Three of the whites were young men, surely capable of serious resistance, and there must have been several opportunities for it. When one of the Carrs was out at an ATM machine with a woman, it meant there were three white men in the house with a lone assailant. While the man was busy raping a woman, how difficult would it have been to overpower him?

At some point is must have become obvious the Carrs intended to kill all witnesses. They could have had nothing else in mind when they marched the group into the snow, and tried to stuff all five into the trunk of a car. There was no more money to be had from ATM machines. All that was left was to make sure no one could testify against them.

Why, therefore, did five young whites-men or women-kneel obediently in the snow to be shot one by one? Were their spirits completely broken from hours of humiliation? Were they so stiff from cold they could hardly move? Or had they simply been denatured by the anti-white zeitgeist of guilt that implies whites deserve whatever they get? One does not wish to think ill of the dead, but these three men showed little manliness.

It is worth noting that in the home of three young Kansas men there does not appear to have been a single firearm. No doubt these men believed what they have been told: that guns are nasty things, best left in the hands of the police, who will always be there to protect us. H.G., who is clearly a woman of great determination, testified that at one point, when she was on her hands and knees and one of the Carr brothers was unzipping his pants, he laid a silver automatic pistol on the floor two feet away from her. She thought about making a grab for it but realized she had no idea how to operate a gun, and instead submitted to rape and attempted murder. Had she known how to use a weapon, her four friends might be alive today.

As for the question of hate crimes, racially conscious whites would see bias charges as at least some level of official outrage at the shocking crimes committed by these two blacks against a series of exclusively white victims. It is natural for whites to assume that behavior so vicious and odious must have been driven by consuming hatred. Most whites cannot imagine treating another human being the way the Carrs treated their victims unless there were some terrible underlying animus. Moreover, it is probably safe to assume that if the races were reversed it could only have been a crime of racial hatred, and this is probably why so many whites are furious at authorities who have been so quick to rule out bias.

However, it may be a mistake to project white sensibilities onto blacks. It may be that trial testimony or unsealed documents will show a clear racial motive, but it is also possible no evidence of racial hatred will ever come to light. It may also be that the Carr brothers are incapable of analyzing and describing their own motives with enough intelligence to make it possible for others to judge them.

The angry whites do not seem to realize that what happened on the night of Dec. 14 may be only a particularly brutal expression of the savagery that finds daily expression in American crime statistics and African tribal wars. It may very well be that the Carr brothers are so depraved they can commit on a whim brutalities that whites can imagine only as the culmination of the most profound and sustained hatred. This view, along with whatever it may say about blacks as a group, is the one the Wichita authorities have tacitly endorsed — and they may be correct. It is a far darker view of the Carr brothers to assume that this is simply the way they are, that they can commit unspeakable acts without any special motivation, that the Wichita Massacre was nothing more than two black men on a tear that went wrong.

Source: https://www.amren.com/news/2020/12/the-wichita-massacre-black-on-white-crime/