The War between John Deere & White Farmers in the US – They can remotely control the tractors!

[Take note of the power of the software and technology that allows John Deere to remotely control the vehicles. This war over the repair of vehicles is fascinating. These mega-corporations run by Jewish scum cannot be trusted. I am convinced there is a world wide war against White farmers. It is not just in South Africa. Jan]

It’s Husker Harvest Days, Nebraska’s biggest agricultural trade show, and Kevin Kenney is working the pavilions. The engineer, inventor, and inveterate manure-stirrer is trying to be discreet. He has allies here among the sellers and auctioneers of used tractors and aftermarket parts. There are farmers, mechanics, and the odd politician or two who embrace him. But enemies lurk everywhere.

Kenney leads a grassroots campaign in the heart of the heartland to restore a fundamental right most people don’t realize they’ve lost—the right to repair their own farm equipment. By sheer dint of personal passion, he’s taking on John Deere and the other global equipment manufacturers in a bid to preserve mechanical skills on the American farm. Big Tractor says farmers have no right to access the copyrighted software that controls every facet of today’s equipment, even to repair their own machines. That’s the exclusive domain of authorized dealerships. Kenney says the software barriers create corporate monopolies—and destroy the agrarian ethos of resiliency and self-reliance.

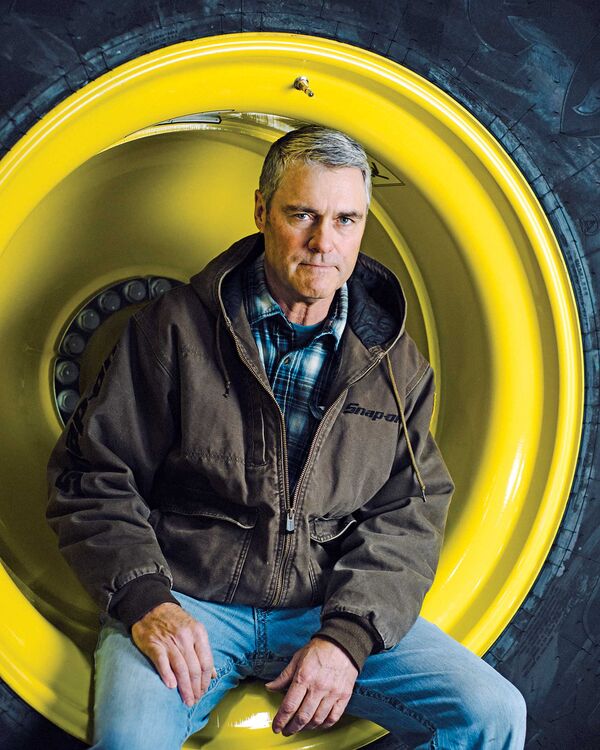

“The spirit of the right-to-repair is the birthright we all share as a hot-rodding nation,” he says, channeling his inner Thomas Jefferson and Big Daddy Don Garlits. Tall and trim at 55, with gray-flecked hair and a passing resemblance to a corn-fed George Clooney, Kenney has kicked up significant pushback against the computerization of U.S. agriculture. His crusade to pass right-to-repair legislation in Nebraska has spread to proposals in 20 states. Last spring, Senator Elizabeth Warren, campaigning for the Democratic presidential nomination, called for a national law “that empowers farmers to repair their equipment without going to an authorized agent.”

At stake for Deere & Co. and other big manufacturers is the free rein they’ve had to remake farming with data and software. The transformation has helped U.S. farmers increase productivity, but at the cost of a steady shift in operational control from farmer to machine. One of the world’s oldest and most hands-on occupations has literally become hands-off.

Anything a farmer does on a modern tractor, beginning with opening the cab door, generates messages captured by its main onboard computer, which uploads the signals to the cloud via a cellular transmitter located, in many Deere models, beneath the driver’s seat. These machines have been meticulously programmed and tested to minimize hazards and maximize productivity, Deere says, and it’s all too complicated for farmers to be getting involved in. The issue isn’t actually repair, says Stephanie See, director of state government relations for the Association of Equipment Manufacturers—it’s agitators who insist on the right to modify the machines.

“One tweak could cascade throughout an entire software system and lead to unintended consequences,” says Julian Sanchez, Deere’s director of precision agriculture strategy and business development. In a fast-moving vehicle weighing as much as 20 tons, he says, that could mean carnage. It doesn’t take much imagination to envision a coding mistake by a hacker, or even a well-intended farmer or mechanic, that sends a 500-horsepower combine careening into a farmhouse or through a clutch of workers eating lunch in the fields.

Kevin Kenney, prairie provocateur.

PHOTOGRAPHER: WALKER PICKERING FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

For a decade, the right-to-repair battle cry has rattled around rarefied circles of digital-rights activists, techno-libertarians, and hands-on repair geeks—primarily on the East and West coasts. Now, largely because of Kenney’s persistence, it’s tugging at the Farm Belt. Why, activists ask, should the buyer of an espresso machine or laser printer have to get replacement pods and cartridges from the original manufacturer? Who is Apple Inc. to dictate that only its certified parts can be used to repair a broken iPhone screen? What gives Deere the right to insist, as it did in a 2015 filing with the U.S. Copyright Office, that its customers, who pay as much as $800,000 for a piece of farm equipment, don’t own the machine’s software and merely receive “an implied license” to operate the vehicle?

“We’ve been telling people for years that if it has a chip in it, it’s going to get monopolized,” says Gay Gordon-Byrne, executive director of the Repair Association, a national coalition of trade, digital-rights, and environmental groups that promotes the repair and reuse of electronics. Gordon-Byrne serves as an informal adviser, mentor, and reality check to Kenney. She’s also helped him set a clear goal: a law modeled on a landmark Massachusetts statute, passed in 2012, that required the auto industry to offer car owners and independent mechanics the same diagnostic and repair software they provide their own dealers. After it passed, automakers relented and made all their repair tools available nationwide.

That’s what Kenney demands for farm equipment—and what Deere and its competitors reject.

At Husker Harvest Days, an ag industry blowout held every September in Grand Island, Neb., Kenney moves warily. After lunch, he drops by to see Kenny Roelofsen, co-owner of Abilene Machine LLC, a five-state retailer of used equipment and spare parts based in Abilene, Kan. Roelofsen’s company is instrumental in keeping older tractors in the field, an essential service for smaller farmers on tight budgets. But he says software barriers in newer machines are killing his incentive to make and sell parts. “I’ve stopped developing parts for machines built after 2010, because I know my customers can’t work on them without software,” he says. “Only giant corporate farms can afford newer equipment. For the small guy, it’s not economically feasible.”

Deere’s pavilion at Husker Harvest Days occupies a huge corner lot decked out in green and packed with gleaming new machines. Kenney is talking quietly there beside an enormous 9000 Forage Harvester, priced at about $600,000, when a familiar face approaches. It’s Willie Vogt, executive director of content for Farm Progress Cos., the agricultural publishing company that produces Husker Harvest Days and several other big farm shows. Deere is one of three corporate sponsors here; it also sponsors Farm Progress’s namesake show, which will be held in Iowa in September.

Vogt stops to chat. Kenney tenses up. Vogt, whose bio says he’s covered agriculture for 38 years and oversees 24 magazines and 29 websites, says he’s still not ready to publish stories on right-to-repair. “It’s a very complicated issue that generates more heat than light,” he says.

The two men square off on the green carpet. Vogt says Deere can’t let people meddle with the machines for safety reasons, pointing to the 9000 harvester’s enormous rotors by their feet. He tells Kenney that “the left side of the issue” pays lip service to repair but really wants access to manufacturers’ source code to modify horsepower, emission controls, and other programmed functions. Kenney fires back: “Why should farm vehicles be treated any differently than cars and trucks?”

Kenney is disgusted. “Willie Vogt’s basically a knight for Deere,” he says, leaving the pavilion. “It’s like Napoleon when he ran through Europe. He didn’t fight. He knighted everyone.” Vogt, in a follow-up email, disputes this characterization. “People should be able to repair what they can, and that isn’t easy,” he writes. “But full access to code remains a concern.”

American farmers have a saying to describe their loyalty to Deere, an attachment stretching back generations in many families: “We bleed green.” Deere’s metallic-green-and-yellow farm vehicles dominate the world’s $68 billion market for agricultural equipment, accounting for more than half of all farm machinery sales in the U.S. and more than a third of equipment revenue worldwide—a bigger market share than that of the next two tractor makers, Case New Holland and Kubota Corp., combined. Customer loyalty is legendary. A 2017 survey by Farm Equipment magazine found 84% of Deere owners plan to purchase another green machine.

The company says the world needs digitized farming to feed the 10 billion people expected on Earth by 2050. The proprietary software Kenney and other repair advocates revile enables sensors and computers on machines to log and transmit data on everything: moisture and nitrogen levels in soil; the exact placement of seeds, fertilizer, and pesticides; and, ultimately, the size of the harvest. Having access to so much real-time data enables farmers and their computer-controlled machines to plant, spray, fertilize, and harvest at optimal times with as little waste as possible. All the farmer has to do is link his equipment to agronomic prescriptions beamed to him over the internet.

This is farming’s version of big data, and the potential is staggering, enthusiasts say. The efficiency gains of recent decades have increased productivity an estimated 1.4% per year for the past 70 years, and U.S. farmers now produce an average corn yield of about 175 bushels an acre. That’s still less than 30% of what some hyperattentive farmers have shown is possible under optimum conditions. Deere and other agriculture technology companies are betting that what the industry calls “precision agriculture” can dramatically expand output.

“If you were to walk around our buildings with hundreds, thousands of software engineers, it’s like every line of code being written there is making it into a machine that’s helping a farmer farm more precisely and reliably,” says Deere’s Sanchez. Consider machine sync, he says, the algorithms that direct the high-speed whirl of different farm machinery. As a combine processes a field of corn or soybeans during harvest, it sprays the separated grain into a wagon towed alongside the combine. When the wagon is full, it’s driven to the edge of the field and emptied into a truck while another wagon slides in to take its place. The vehicles are in constant motion, synchronized by software that controls the steering, drive train, and actuators on each like a ballet choreographer. The same technology enables a planter machine to place 40,000 seeds in an acre of land with the precision of less than an inch.

“I realized it all goes back to software. That was the beginning of my John Deere derangement syndrome”

There’s also a more obvious motive for protecting proprietary software: money. Historically, the healthy profit margins of the parts and services units have helped smooth out earnings when demand for machines is down. For Deere and its dealerships, parts and services are three to six times more profitable than sales of original equipment, according to company filings. Farmers need to keep aging equipment running; that helped increase annual parts sales by 22%, to $6.7 billion, from 2013 to 2019, while Deere’s total agricultural-equipment sales plunged 19%, to $23.7 billion. If a right-to-repair law pried open the parts and services markets to competition, Deere’s cyclical balancing act could falter. Sanchez denies the company is fighting to protect a parts-and-services monopoly. “On the repair side, I would say we’re all in,” he says. “There’s a significant number of tools that exist in the market and are available to any farmer without having to go through the dealer.”

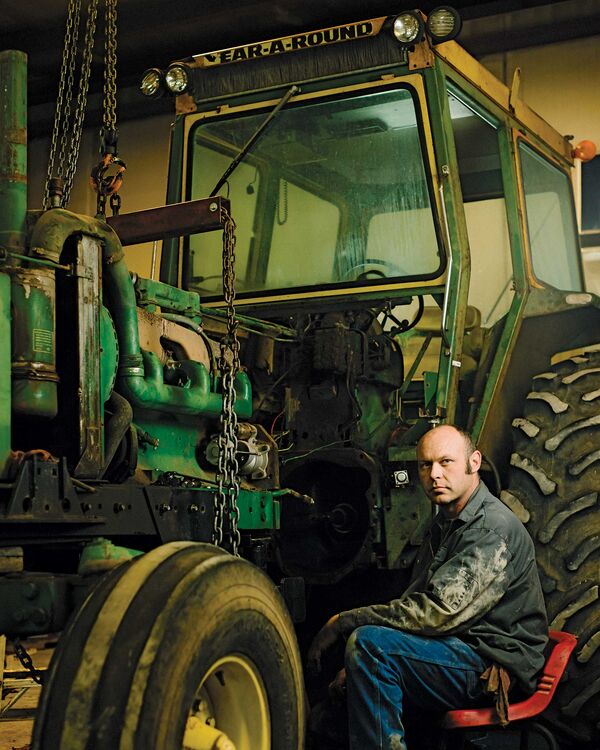

That’s news to Jeremy Davis, owner of Firehouse Repair LLC in Palmer, one of a small number of independent equipment mechanics in central Nebraska. Before going out on his own in 2016, Davis worked for a decade at an equipment dealership, where “you take for granted you can get any software or service manual you need,” he says. “Now it’s really a struggle. We can’t even get basic wiring schematics for particular brands.”

Jeremy Davis, owner of Firehouse Repair in Palmer, Neb. Smaller farm operations rely on him to keep older equipment, like this 1963 Deere model 4010, running.

PHOTOGRAPHER: WALKER PICKERING FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

At least half the repairs Davis sees involve code faults triggered by emission-control systems. The faults render vehicles inoperable—a bit like a mouse incapacitating an elephant. He can replace the exhaust filters and particulate traps that throw a tractor’s codes, but dealerships won’t provide the software to restart it unless he or the owner hauls the machine in or pays for a mechanic to make a house call. A few years ago, Davis paid $2,500 for a pirated version of John Deere’s 2014 Service Advisor software from someone in Hong Kong, but the discs are now long out of date.

Davis scoffs at a main industry argument against providing repair software to farmers and independent mechanics: that they’ll abuse it to disable emission-control systems. The incentive works the other way around, he says. Many farmers who own machines going off warranty delete the emission-system software to avoid costly future repairs—often with the backdoor assistance of the dealers, he says. If right-to-repair legislation led to more independent mechanics who could resolve faults quickly and easily, owners would have less motivation to disable emission controls, Davis says. “The way it is now is unfair to owners, and it’s unfair to me.”

To Kenney, the notion that farmers can’t work on their own tractors is an affront to the rugged individualism that built America. Raised on a central Nebraska farm, he was always passionate about machines. When he was 12, he and a friend rebuilt the transmission of his dad’s 1953 Studebaker pickup, racing to reassemble the parts in a single weekend before his parents returned from a trip.

He earned his agricultural engineering degree at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, and he’ll still drive a dozen hours in a weekend to attend a Cornhusker football game. He’s angry with his alma mater, though, for no longer making agricultural engineering students get their hands greasy working on tractor engines. An administrator told Kenney, in an email exchange that still pains him, that engine repair is taught at community colleges now. “We couldn’t graduate if we didn’t know how to break down and rebuild a diesel engine,” he says.

After failing as a tenant farmer in the early 2000s, Kenney patented a design for a low-emission engine that burns diesel with a mix of ethanol and water. He couldn’t commercialize the so-called dual-fuel technology. In his mind, the big equipment manufacturers were making so much money rigging their conventional diesel motors with clumsy emission-control systems to meet U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standards that they had no interest in cleaner-burning alternatives. “I realized it all goes back to software,” Kenney says. “That was the beginning of my John Deere derangement syndrome.”

He now makes his living installing tractor software for a farm data company and tuning and tweaking trucks and tractors. His calling, however, is the right to repair. He’s spent the past four years turning conservative farmers against the corporate incarnation of motherhood and apple pie.

“If data gets out, negotiating powers are weakened. Farmers’ fears are very real. It’s not paranoia”

For Nebraska farmers, horror stories about tractors “bricking,” or shutting down from a computer fault, are as common as waterhemp in their cornfields—and just as annoying. A Deere spokesperson says, “Help is never more than a finger tap away,” referring to the communications equipment on modern farm implements. But getting a machine running again isn’t always quick. Bill Blauhorn of Palmer lost half a day of harvesting corn while waiting for mechanics to drive 65 miles to his farm to reset the software on his 2017 Case IH combine. The machine’s emission-control system would repeatedly ice up on cold nights and in the morning throw a fault code that prevented it from starting. In 2018, Blauhorn was racing to bring in the harvest before an approaching windstorm when the system wouldn’t turn over. He says the five-hour wait for someone to show up and do a half-hour software fix contributed to a loss of at least 15% of the crop. Since then he doesn’t take chances. “We just let the machine run all night,” he says.

Andrew McHargue’s tractor went down for an entire week during planting season while he waited for technicians to solve a problem. The Chapman, Neb., farmer paid $300,000 for the new machine in 2014, and over the next few years sank almost $8,000 into clearing fault codes. He finally mothballed the combine in favor of a 2010 model without the latest software and emission-control systems. The used tractor cost him an additional $160,000.

“I’m trying to sell the 2014, but nobody wants it,” says McHargue, a board member of Nebraska’s Merrick County Farm Bureau. “The whole disconnect is about who really owns it. If it’s mine, I should be able to modify and fix it myself. There’s no reason we shouldn’t have a repair system exactly like the auto industry’s.”

As things stand, Deere has the technical ability to remotely shut down a farmer’s machine anytime—if, say, the farmer missed a lease payment or tuned a tractor’s software to goose its horsepower, a common hack widely available through gray-market providers. A Deere spokesman says many manufacturers can remotely control vehicles they sell, but Deere has never activated this capability, except in construction equipment in China, where financing terms require it to.