The Last Supper: The Masterpiece Leonardo Didn’t Want to Paint

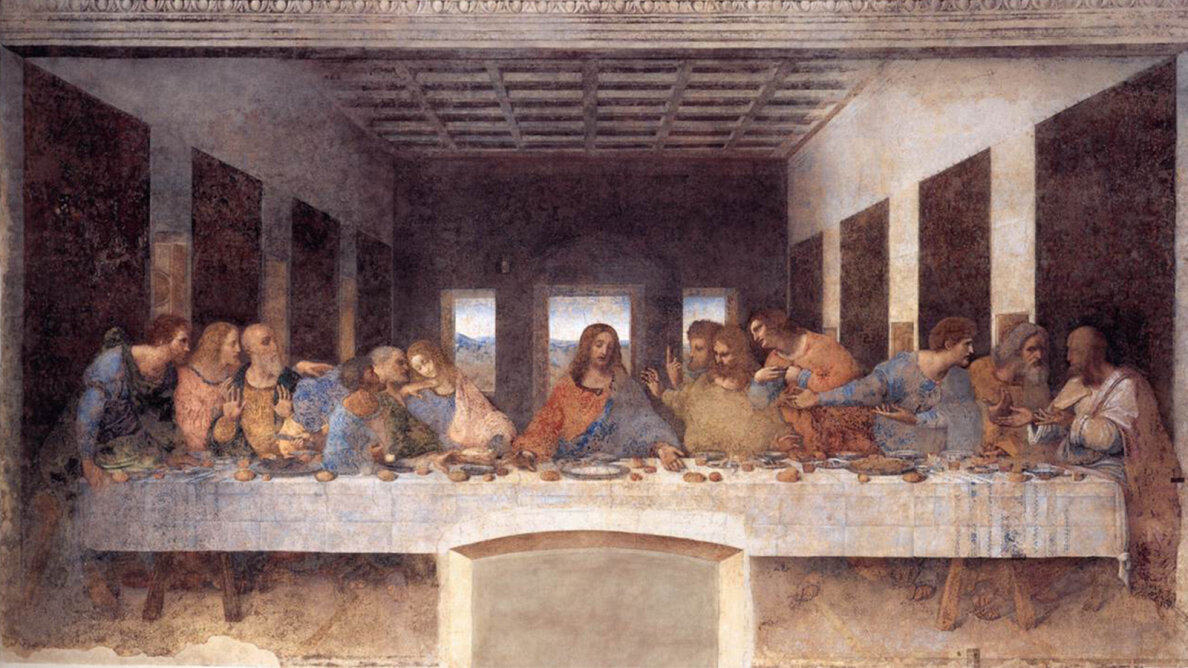

Da Vinci painted "The Last Supper" with a method of his own devising, which involved painting in oil and tempera on a dry wall. The method was not entirely successful, resulting in flaking paint and a fresco that has not completely withstood the test of time. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Located on the wall of Milan’s Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie is a work of art that’s considered by many to be one of the greatest artistic masterpieces of all time. But its creator, Leonardo da Vinci, wasn’t exactly stoked about it when the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, commissioned the piece in 1494.

"Leonardo did not want to paint ‘The Last Supper,’" says Ross King, author of "Leonardo and The Last Supper." "Instead, he wanted to do a gigantic bronze equestrian moment — a monumental work that would certainly have made him famous. But the outbreak of war in 1494 meant he couldn’t do his bronze horse, so as compensation he was given the task of painting a wall in a room where a band of friars ate their dinner every day. He had never painted on such a large scale. Having little experience in such a difficult task, it’s not surprising that he complained bitterly about the commission, at which it was entirely possible that he would fail miserably. Happily, the story turned out otherwise."

What resulted from da Vinci’s hesitant participation is a mural that famously depicts the last supper of Jesus Christ with his apostles, on the day before his crucifixion. The scene is based on the description in the Gospel of John 13:21, and da Vinci intended to convey the reactions of Jesus’ disciples the moment they learned that one of them would betray him.

King, who has also written several other books on Italian, French and Canadian art and history, including "Brunelleschi’s Dome" and "Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling," says da Vinci’s "The Last Supper" is particularly important for a variety of reasons, perhaps most of all for its elevation of the artist to celebrity status. "Its completion marks the moment when Leonardo, then in his mid-40s, finally created what he called a ‘work of fame,’" he says. "It’s amazing to think that, before ‘The Last Supper,’ Leonardo had achieved very little. Had he died in, say, 1492, when he was 40, he would be little more than a footnote in art history, known as someone who showed enormous promise but never delivered the goods. But with ‘The Last Supper,’ he delivered spectacularly. Without having created ‘The Last Supper,’ he probably would never have received his later commissions, including the ‘Mona Lisa.’ So, the work was absolutely crucial not only to the history of art but also to his own career."

One special feature of "The Last Supper" is its sheer size. "No one else in history had ever created such a large painting with such a great level of realistic detail, as well as with such believable emotions and dramatic expressions," King says of the piece, which measures approximately 15 feet by 29 feet (4.5 meters by 8.8 meters). "No one who painted a Last Supper in the centuries afterward could do so without an eye on Leonardo’s masterpiece."

Da Vinci opted to portray one pivotal moment in his scene: the instant just before the birth of the Eucharist, when Jesus reaches for the bread (meant to symbolize his crucified body) and wine (a representation of his blood). According to Corinthians 11:23-26, the event went like this:

"…that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also he took the cup, after supper, saying, ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes."

Who Are the Subjects?

The notebooks of da Vinci are a key to who the key players are in the painting, although experts still argue over some of the details. In one group, Bartholomew, James (son of Alpheus), and Andrew sit together, and look genuinely shocked at what Jesus has just revealed. In another group, there’s Judas Iscariot, Peter and John. Judas, the known betrayer, has a lot going on: He’s fading into the background a bit, he’s holding a bag of money, and he’s knocking over a salt shaker, which experts say is meant to symbolize the expression that "tipping over the salt" means betraying one’s master. Jesus sits in the middle of the group, and on his other side, viewers see apostle Thomas, James the Greater and Philip. Rounding out the group are Matthew, Jude Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot. The symmetry of the figures is signature da Vinci — the artist favored balance in his work and made sure the horizontal painting featured equal numbers of people on either side of Jesus and a thoughtful use of eye-pleasing perspective.

But the content and composition of "The Last Supper" aren’t the only reasons the painting remains legendary. "It has had a very sad history," King says. "The paint began flaking from the wall because of a perfect storm of bad climatic conditions in the refectory — mainly cold and damp. That might not have been such a problem had Leonardo worked in the true fresco technique, which makes for very durable paintings. But he devised a method of his own that involved painting in oil and tempera on a dry wall — something artists were discouraged from doing. His technique, unsurprisingly, did not prove successful."

Due to da Vinci’s ill-advised choices and the poor custodianship in the centuries that followed the creation of the painting, "The Last Supper" started to look rough. And then things got worse. "The work was insensitively ‘restored’ by conservators who didn’t know what they were doing, and caused more harm than good," King says. "In 1652, in a kind of act of vandalism, the friars from the convent knocked a hole in the wall (amputating Christ’s feet) to create a doorway through the painting. The refectory flooded in the 19th century, and Napoleon used the building as a stable — which meant that it was filled with horses and manure. Then during World War II, it barely survived a bomb that destroyed much of the refectory. The fact that we still have it to enjoy is little short of miraculous."

Now That’s Fishy

There are tons of details in "The Last Supper" that art scholars continue to debate and dissect. Take the fish on the table for example: Is it herring or eel? In Italian, the word "eel" is "aringa," although when it is spelled "arringa" it means "indoctrination." The word "herring" in northern Italian is "renga," meaning he who denies religion.

Originally Published: Feb 25, 2020