IMPORTANT: 2 Charts: South Africa is hitting the wall financially & economically…

[Take a look at these charts. They even show that South Africa is doing WORSE than most Third World countries and even worse than other countries in Africa. In terms of debt, etc – South Africa is hitting the wall. Even the Black Jewish President is saying this. Even he is admitting that things are falling apart. All that COVID and lockdown did was to accelerate a trend that we were firmly in, going downward. Let the ship sink! Jan]

South Africa this month lowered tough lockdown restrictions and welcomed its first supply of Covid vaccines — but when it comes to public finances President Cyril Ramaphosa has sounded anything but cheerful of late.

“We do not have the money . . . that’s the simple truth that has to be put out there,” Ramaphosa told local radio in January in a sign of the unprecedented fiscal pressures facing his ruling African National Congress this year.

High debt servicing costs, costly bailouts for state-backed companies and surging public sector wages have taken their toll on an economy beset by stagnant growth and falling tax revenues. “We’ve been in a fiscal squeeze for a very long time, even before the pandemic . . . [it] has put us in an even more precarious position,” said Thabi Leoka, an independent economist.

South Africa is emerging from an intense second coronavirus wave over its festive season. Of 1.45m confirmed cases to date, around 650,000 were recorded after the start of December. Growth in new cases and deaths has now peaked and some restrictions — such as a ban on alcohol sales and religious gatherings — have been lifted. But even with vaccinations due to begin “there is an ever-present danger of a resurgence”, Mr Ramaphosa warned last week, in part because of a local and more infectious variant. It is unclear if the country can afford to lock down the economy again.

“The problem is not really the Covid shock but underlying fiscal imbalances that South Africa has not resolved for over a decade,” said Michael Sachs, a former head of the South African Treasury’s national budget office and an adjunct professor at Wits university in Johannesburg.

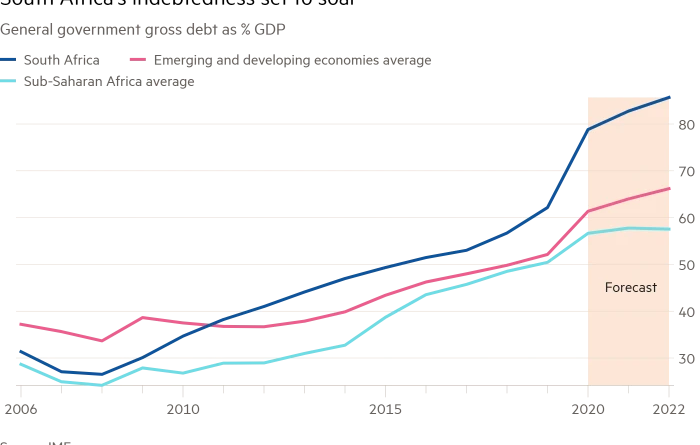

South Africa’s debt has surged because growth has fallen far behind the interest rates the country pays to borrow. Per capita, GDP has been falling for years. As an indicator of how much it borrows on the domestic market, the estimated 20bn rand that it would cost to finance its mass vaccination plan is equivalent to about 10 days of borrowing. It is also slightly more than double last year’s government bailout for South African Airways, the broken flagship carrier, and about one-tenth of the aid that Eskom, the state power monopoly, will receive to help pay debts between this year and 2026.

Debt was already just under two-thirds of GDP before the pandemic with about 15 cents in every rand of South Africa’s tax revenue being spent on servicing it. Unless action is taken, the South African Treasury warns the ratio could rise to 100 per cent of GDP and the debt service bill to a quarter of revenue in the next few years. While rising commodity prices will buoy miners’ contribution to state revenue this year, a lack of investment in the sector, one of the country’s biggest export earners, means that production continues to fall.

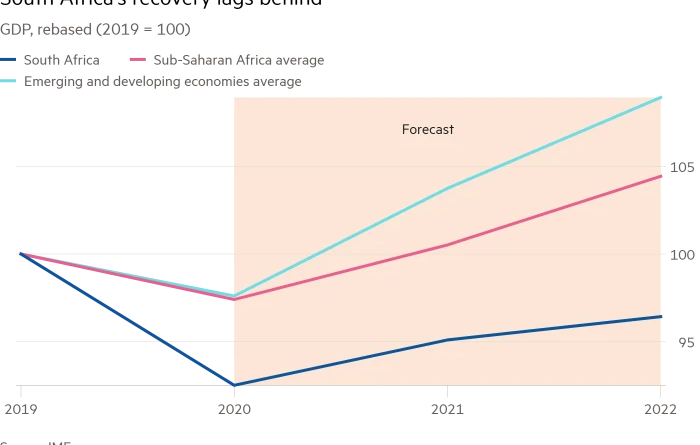

South Africa’s central bank is forecasting growth this year of 3.6 per cent and 2.4 per cent next year, one of the slowest projected rebounds in major economies. This month, statistics are likely to show that the jobless rate at the end of the year had risen even beyond 43 per cent recorded in the third quarter, which included those who have given up looking for work. “Protracted vaccination procurement and distribution processes, as elsewhere, will probably weigh on the economic recovery this year,” the IMF said last week. What was looking like a three-year journey to regain pre-pandemic output might now be half a decade, say some business leaders.

“We are finally seeing the effects of bad governance and low growth,” Daniel Silke, an independent political analyst, said. South Africa is “basically stuck,” added Leoka. “We are unable to generate growth meaningfully using our budget.”

The solutions are politically difficult. Tito Mboweni, the finance minister, has prioritised reining in the public wage bill, risking the political bargain on which ANC rule lies. Such cuts have “never happened before, certainly not in South Africa’s democratic history,” said Sachs. It implies not only holding down wages in the public sector but also erosion in the quality of public services that the poorest South Africans rely on. “You have to ask if that is a politically sustainable strategy in South Africa,” Sachs added.

Already relief for the poorest in the pandemic has been in doubt. A Covid welfare grant of 350 rand ($23) per month for jobless South Africans expired last month. The ANC is likely to ultimately extend the grant because “it is not going to throw its support base to the curb side” given local elections later this year and the surge in joblessness, Silke said. However the debate has underlined that the tight fiscal margins are now reaching “the heart of the political survival of the ANC,” he said.

For now, South Africa should be able to repay its debts as the high rates it offers lures investors weary of global low interest rates. At a government bond sale last week, investors tendered record bids for the amount on offer. “It is completely unsustainable however you look at it, but markets are still funding it,” Sachs said.

While deep local capital markets mean there is no imminent funding crisis, investors’ concerns are reflected in the high interest rates they demand, currently at about 9 per cent a year for the benchmark 10-year local bond. “These levels are not sustainable over the medium term,” said Raza Agha, head of EM credit strategy at Legal & General Investment Management.

Peter Attard Montalto of Intellidex, a capital markets research firm, warns that ultimately investors could lose faith in the prospects for growth. “The pandemic hasn’t created South Africa’s problems,” he said, “but it has accelerated them and allowed us to leap several years down the existing path.”