EXCELLENT: CHART: How Right-Wing Violence in Western Europe Changed in 2019 – incl. Netherlands & Norward – My Comments

[The numbers are dropping, but this is possibly due to more intense clampdowns I would guess. However, the White right's moves indicate a growing frustration with the system. I am especially pleased to see that the motivation is growing in intensity. e.g. Netherlands and Norway. Notice how the white right is also seen as an ever bigger threat and all these intelligence agencies are working together. They're working together to keep the Anglo-American-Jewish paradigm in place. This means: DIVERSITY! Jews want that diversity. Jews need it, in my view because they see it as a buffer against pogroms against themselves AND THEIR OWN EXPULSIONS coming. Jews actually want to remain inside Western Civilisation because this is where, this race of shit can come and live the best life of all. They win and do so much better in Western countries, especially NATIONALIST ones because the Nationalists are the best run countries. It is my view that Jews are drawn to the most successful countries, and yet, the most successful countries, where the whites are the most proud and hard working, are also the ones where they get even more enraged. at the long term behaviour of the Jews. So Jews need other races in there, FOR MANY REASONS, all of which are beneficial to the Jews and not to the whites. All in all, it shows that there is still life in the nations of Europe. For the white man, the ONLY path to FREEDOM is through war. Jews will NEVER allow white men to be themselves. Jan]

While the year 2019 in Western Europe was neither very violent in terms of fatal attacks, nor particularly deadly in terms of fatalities, we witnessed a worrying emerging global trend of right-wing lone-actor terrorists carrying out, or trying to carry out, mass-casualty attacks. Here are some main findings from the RTV Trend Report 2020.

Right-wing terrorism on the agenda

Right-wing terrorism and violence were on the agenda in many Western countries in 2019. For example, the annual report from the Munich Security Conference, the world’s largest gathering of international security policy makers and analysts, presented ‘right-wing extremism’ as a key issue alongside ‘space security’, ‘climate security’ and ‘the technology race’. In many countries, the security services (e.g., The Netherlands and Norway) pointed to the growing threat of right-wing extremism.

The main reason behind the increasing attention was an apparent emerging global trend of lone-actor terrorists carrying out, or trying to carry out, mass-casualty attacks, inspired by the terrorist attacks in Christchurch, New Zealand, on 15 March 2019. To what extent was this trend also present in Western Europe in 2019? And how did right-wing violence in this region change in 2019 compared to previous years?

In this blog post, we provide some key findings derived from the latest update of the Right-Wing Terrorism and Violence (RTV) dataset. Every year, C-REX, together with a network of country experts, updates the data using a variety of different sources, most notably media reporting. The dataset is free of charge: a limited version can be downloaded here, whereas full version can be requested for research purposes here.

Fatal attacks and fatalities in 2019 in Western Europe

In 2019, there were four fatal right-wing attacks and five fatalities in Western Europe:

In June, CDU-politician Walter Lübke, was shot dead in his house at night by a 45-year-old man formerly active in the extreme right party Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD)

In July, an immigrant originally from Guinea was beaten and killed on the streets of Canteleu, France

In August, a 21-year-old man in Bærum, Norway, first shot and killed his stepsister, adopted from China, before driving to the Al-Noor Islamic Centre nearby with the aim of killing as many Muslims as possible.

Entering the mosque, he was overpowered by two elderly worshippers, and no one but the perpetrator was severely injured.

In October, a 27-year-old German from Saxony-Anhalt, shot and killed a random woman and the owner of a Turkish kebab restaurant in Halle, Germany, after failing to shoot his way through the door of a synagogue.

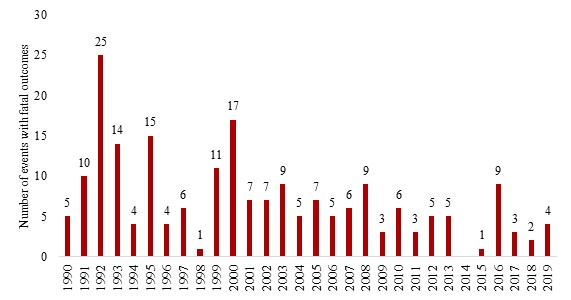

From a long-term perspective, the year 2019 in Western Europe was neither very violent in terms of fatal attacks, nor particularly deadly in terms of fatalities. In fact, most years, particularly in the 1990s, had many more fatal attacks than the four from 2019 (see Figure 1). Since 2001, the number of fatal attacks per year has been quite stable, with an average of five fatal attacks per year, thereby placing 2019 slightly below average. This year is also in the lower half of the distribution with five fatalities in total, which is just below the yearly median for the entire period (six), and equal to the one of the past ten years.

However, from a short-term perspective, that is, the most recent five-year period, only 2016 had more fatal attacks than 2019. Moreover, while two of the fatal attacks from 2019 targeted single persons, the Bærum and Halle attacks were intended to kill as many as possible. Only tactical failures – being unable to enter the synagogue (in the Halle case) and being overpowered inside the mosque (in the Bærum case) – prevented these events from resulting in more fatalities. Such intentional mass-casualty attacks are rare in Western Europe and may thus indicate a new trend if they continue to be carried out in the near future. Considering that both perpetrators were highly influenced by online subcultures, there is a need to pay particular attention to risk factors associated with vulnerable individuals’ interaction with extremist ideologies found on websites and social media (read more about “Online-inspired terrorism” in the RTV Trend Report 2020).

Mostly lone actors, but also organized groups

Lone actors carried out slightly more than one third of all attacks in 2019, making them the most common perpetrator of fatal and severe forms of right-wing violence. These attacks include not only already mentioned cases like Bærum and Halle, but also severe cases such as the 50-year-old German who drove his car into a group of Syrian and Afghan citizens on New Year’s Eve in Bottrop, injuring four, and the Italian man who set fire to a caravan of a Sinti family and shot one family member with a hunting rifle.

Although being coded as ‘lone actor’ means the perpetrators prepare and carry out attacks alone at their own initiative, many of these perpetrators are inspired by others (e.g. Brenton Tarrant) and/or influenced by socio-political developments. Moreover, several ‘lone actors’ have been affiliated to organizations (e.g. CasaPound) or less structured movements (e.g., Reichbürger). In this sense, many of these actors are ‘lone’ only in a relative sense. They are – to various degrees – part of national or transnational extreme-right subcultures or networks, online and sometimes also offline.

The second most common type of perpetrator was ‘organized groups’, in which we include not only full-fledged organizations, but also groups of two or more individuals that are ‘affiliated’ to a broader organization but act on their own initiative. This type of perpetrators promoted no less than a quarter of the episodes registered in 2019 (27 events). While some of the groups have a long and well-known history of being involved in right-wing violence, such as CasaPound and Forza Nuova in Italy and Golden Dawn in Greece, others have emerged more recently and are much less known, such as the Nationalist Socialist Knights of the Ku-Klux-Klan Deutschland, Nordkreuz in Germany and Breizh Firm in France.

The most frequent targets are ethnic and religious minorities

The primary target group for fatal attacks in 2019 was ethnic and religious minorities, with one of the attacks targeting an immigrant, one a mosque, and one a synagogue. The fourth fatal attack targeted state institutions (including elected politicians) with the murder of Walter Lübke (Read more about “Attacks against politicians” in the RTV Trend Report 2020). The pattern is quite similar for non-fatal events for 2019. A large majority of all the events (76 of 116) primarily targeted ethnic and religious minorities.

Political opponents were the second most frequently targeted group, with a majority of events targeting left-wing and anti-fascist activists. In addition, right-wing violence against separatists has re-emerged, with ongoing conflicts such as the one in Northern Macedonia, Greece, and especially in contexts where regional issues are closely tight to left-right cleavages, such as in Catalonia, Spain. One reason why this target group is less pronounced in our data for fatal attacks is that many of these events emerge from street-level brawls between right- and left-wing activists, which rarely result in fatalities.

Long-term trends

If we look at the distribution of perpetrator types over time for fatal events, the most notable trend is, first, that the numbers of (skinhead) gangs and unorganized perpetrators are decreasing, both in absolute terms and relative to other perpetrator types. Such gangs were responsible for around half of all fatal attacks during the 1990s and early 2000s. The second trend is that the number of fatal lone actor attacks has increased in recent years, from only five attacks between 2010 and 2014 to 15 between 2015 and 2019. Most of the recent attacks took place in either 2016 (seven events) or 2019 (four events). Given that fatal violence by other typical perpetrators types (e.g., unorganized and gangs) has decreased, lone actors have been responsible for almost all fatal attacks since 2015.

When looking at the distribution of target groups, we see that the relative share represented by attacks against ethnic and religious minorities has grown over time, but only because attacks against other target groups have decreased. There is also a small increase in attacks against state institutions during the last five-year period, though the numbers are still small.

What’s next? Far right responses to the coronavirus

Predicting how right-wing terrorism and violence will look like in the future is not an easy task. While our findings for 2019 suggest stability in terms of fatal attacks and fatalities, it also shows how one event (i.e. Christchurch) might inspire a particular, and in this case a (potentially) more deadly, modus operandi (read about the ‘modus operandi’ of extreme right terrorism and violence here). Still, the nature of far right violence in 2020 will, as the rest of society, most likely affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

Lower-scale violence targeting people of Asian descent because of their alleged responsibility for spreading the coronavirus has already been observed in several countries in Western Europe (e.g., France, Belgium, Italy, Germany and the UK) and beyond (e.g., the US, Australia and Canada). Moreover, the revolutionary wing of the far right is already trying to exploit this crisis by spreading disinformation and ‘fake news’ to feed existing and emerging far-right conspiracy theories and thereby to ‘accelerate’ polarization and ultimately a break-down of the current ‘System’.

Whether or not terrorism and violence will be used as means to this end, however, remains an open question. While today’s revolutionary right lacks the resources, organization and capabilities to mount a systematic campaign of terrorism and violence, we should not rule out large-scale attacks influenced by COVID-19 conspiracies, either by small autonomous cells or, as a continuation of the existing trend, lone actors. The US has already witnessed a few activists moving from thought to action or plotting do to so, though no one has been killed thus far. Therefore, there is a need to monitor these conspiracies as they unfold in order to better predict and protect likely targets of such attacks.

Source: https://www.miragenews.com/how-right-wing-violence-in-western-europe-changed-in-2019/