The Heroic White Tribe of Africa

[The Afrikaners, is a term that gets confusing. A lot of usage of Afrikaner actually applies to the Boers. Jan]

The Afrikaners are a truly heroic people, with a history of courage, perseverance, and faithfulness unmatched in modern times. In little more than 300 years, they brought forth a distinctive culture, a national church, a rich literature, and a vivid sense of identity. Known as Africa’s White Tribe, the Afrikaners’ worst threats have always been other whites: first the Dutch, then the British, then the combined forces of all white people everywhere – to the point that they are now at the mercy of blacks. This is their tragic story.

It begins in 1652, when the Dutch East India Company established a way station at the Cape of Good Hope for ships making the long voyage around Africa to the East. This is the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck at the cape, along with 70 or 80 men.

The company wanted only a victualling station, not a colony, but employees began to settle permanently, and started calling themselves Afrikaners, or Africans, to distinguish themselves from workers on temporary assignment. Later, they also came to be known as Boers, or farmers. The population started out overwhelmingly Dutch, but the colony began to attract French Huguenots and some Germans, and by 1691, only three quarters of the white population was Dutch. There was full assimilation; everyone learned the Afrikaans language – still a mutually intelligible version of Dutch – and contributed to the growing new culture.

The Dutch East India Company wanted to keep the Afrikaners under its thumb near the coast, but they were independent from the start. As early as 1700, wandering Boers, or Trekboers, explored thousands of miles into an almost empty interior. Here are some of the treks from 1700 to 1800.

In 1795, as part of its wars with the French, the British took over the Cape colony. They were arrogant masters, and Afrikaner resentment grew, especially after the imposition of a foreign language – English – as the official language. In the 1830s and ’40s, an estimated 14,000 Boers sold their farms – if they could find a buyer – and moved into the unmapped interior to be free from the British. Known as Voortrekkers, or early trekkers, they made up wagon trains of all their livestock and possessions, and set off into the wilderness. This map shows the routes of the great treks between 1835 and 1840. This is a slightly fanciful depiction of the hardships of the Great Trek, which has become a central element in Afrikaner history. This imposing monument to the Voortrekkers was completed in 1949. It includes tributes to the women on the trek, and the solemn interior befits the epic conquest of an untamed land.

In 1838, when the Boers entered what is now Natal — a thousand miles from the Cape — they met Zulus, under King Dingane. Boer leader Piet Retief and an unarmed delegation of about 100 men met with Dingane and signed a treaty recognizing the right of the Boers to settle. After the signing, Dingane invited his visitors to a show put on by his soldiers — then leapt to his feet and gave the order to slaughter the whites. His men clubbed them to death and made sure to kill Retief last so he would witness the deaths of all the others, including his 14-year-old son. The Zulus left the bodies to be eaten by vultures, as was their custom. This is a monument to Retief and his men. Other trekkers found their bodies 11 months after the massacre and buried them in a mass grave, over which the monument stands guard.

After Dingane and his men slaughtered the Retief delegation, they attacked several unsuspecting Voortrekker camps in what became known as the Weenen Massacre, killing a total of 534 men, women, and children. As historian AJP Opperman writes, “Not a soul was spared. Old men, women and babies were murdered in the most brutal manner.”

The Boer-Zulu conflict came to a head 11 months later in what became known as the Battle of Blood River. Four hundred sixty-four Voortrekkers, under the leadership of Andries Pretorius, drew their covered wagons into a circle and held off an estimated 10 to 15 thousand Zulu soldiers. The Afrikaners knew they faced terrible odds, and before the battle, they took a vow that if God would grant them victory, they would honor that day forever and would build a church in thanksgiving. It was a miraculous victory, and the Church of the Vow still stands in Pietermaritzburg.

Today, metal replicas of the wagons are laid out at the Blood River Heritage Site. This battlefield monument stands before the entrance to the museum.

Afrikaners went on to establish many independent republics in what was mostly uninhabited land.

The two largest, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, flourished from 1852 and 1854, respectively, until 1902. Large families, like the one in this 1886 photograph, built growing, prosperous nations. What destroyed the Boer republics?

British greed. Britain had colonized the rest of South Africa, and in 1886, there was a gold strike in the Witwatersrand Basin near what became Johannesburg. It was deep in Afrikaner territory, and the British would stop at nothing to get the gold. It took two wars finally to defeat the toughest colonial enemy the empire had faced since the American Revolution. The Afrikaners were led politically by upright, patriotic men such as Paul Kruger, the president of the South African Republic. In the field, they followed great generals such as Koos de la Rey, shown here in the center. These brave patriots were finally crushed in 1902 by a British force of more than half a million men, nearly ten times as many as the Boers could put into the field. In order to cut the Boers off from their supplies, the British herded women and children into concentration camps, where more than 26,000 died. This is Lizzie van Zyl. She and her mother were considered undesirables because her father refused to surrender, and were put on starvation rations. Lizzie died in camp, age seven.

Britain granted independence in stages, and South Africa became a fully sovereign nation in 1934. Whites, both English and Afrikaner, ruled over a black population that was much larger. In 1948, South Africa introduced the apartheid system of separate development. Petty apartheid meant blacks and whites had separate facilities, as in the segregated South. South Africa also instituted grand apartheid, or tribal homelands for blacks. Here is a map of the Bantustans. As you can see, they are small and scattered, and some are chopped up into many small pieces. South Africa granted formal independence to four of them, but none was ever recognized by any other country.

Beginning in the 1960s, the white nations of the world led an increasingly harsh campaign of sanctions and boycotts to force the South Africans to end minority rule. Europeans, especially, began to support armed rebellion by blacks. All this pressure culminated in 1994, when blacks were given the vote, the African National Congress took power, and never let it go.

Black rule has meant what it means everywhere: corruption, incompetence, and the systematic dispossession of whites. Many thousands of whites have fled the country, but this is easier for English-speakers. Some Afrikaners have escaped, but many have nowhere to go.

The regime openly persecutes them. Under the slogan, “Afrikaans must fall,” blacks have even eliminated Afrikaans-language instruction at the University of Pretoria. Blacks routinely kill white farmers – Boers, literally – to drive them from the land. Each cross represents a slaughtered farmer and Plaasmoord means farm murders.

The world has treated South Africans as criminals, but minority rule was the only way badly outnumbered whites could maintain order and preserve civilization in a multiracial state. Could a fair, more generous division of the country along racial lines have left whites with a real country of their own? We will never know. Whites were reluctant to hand over to blacks the great cities and productive farms whites had built.

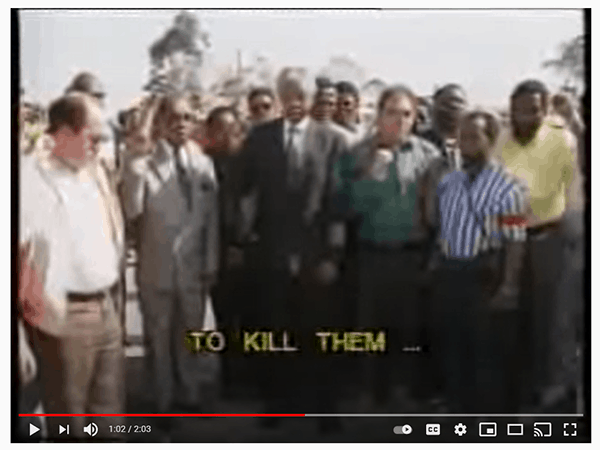

But black rule means the destiny of whites is now in the hands of others, many of whom hate them. In today’s South Africa, King Dingane, who slaughtered women, children, and unarmed Afrikaner men is admired as a liberation hero. Even the sainted Nelson Mandela raised his fist and sang the black revolutionary song, “Kill the Boer.”

The Afrikaners nation survived many attempts to strangle it in its crib. Now, once again, it faces odds like those at Blood River. Will there be another miracle? Its story is a message to us all. Only in unity can white nations survive and prosper.

Source: https://www.amren.com/videos/2021/06/the-heroic-white-tribe-of-africa/