Photos & Maps: S.Africa: Drugs & Drug Wars! Heroin capsules the new trend to emerge in Durban’s violent a nd volatile drug gang landscape

[The drugs seem to be coming from Zulu country – Natal. This detailed article exposes the big mess. These are Blacks who are busy with this. Yeah, Capitalism at work!! The more I look at how money works and the end results, the more I wonder if the love of money isn't an evil thing? Jan]

As violence in Durban’s heroin market has escalated, a unique trend has emerged for packaging heroin in pharmaceutical-style capsules, which may shed light on the structure of the drug market and supply routes. Police corruption and community support of drug networks are both major factors in the local drug economy, as demonstrated by the recent assassination of a notorious underworld figure, Yaganathan Pillay, otherwise known as ‘Teddy Mafia’.

Durban is home to one of the oldest, largest and most deeply entrenched heroin markets in South Africa. As the market has grown in sophistication, a unique method of processing and distributing heroin has come to be widely used in the Durban area: that of packaging the drug in pharmaceutical-style capsules. This unique method sheds light on the structure of the heroin market in and around Durban, yet also raises questions as to why Durban-based drug networks are operating differently from their counterparts elsewhere.

![]()

Evidence gathered by police in Durban in a July 2019 raid that demonstrates the assembly-line production approach and sheer scale of producing heroin capsules. (Photos: South African Police Services)

This evolution has taken place in a volatile context. Drug dealers in key Durban suburbs are deeply entrenched in their communities, employing a mix of charitable giving (to secure community favour), violence and links to corrupt police officers. In recent months, a turf war connected to the drug market has escalated, culminating in the assassination of Yaganathan Pillay, a notorious underworld figure also known as “Teddy Mafia”, and a gruesome reprisal.

Heroin capsules: a Durban-specific phenomenon?

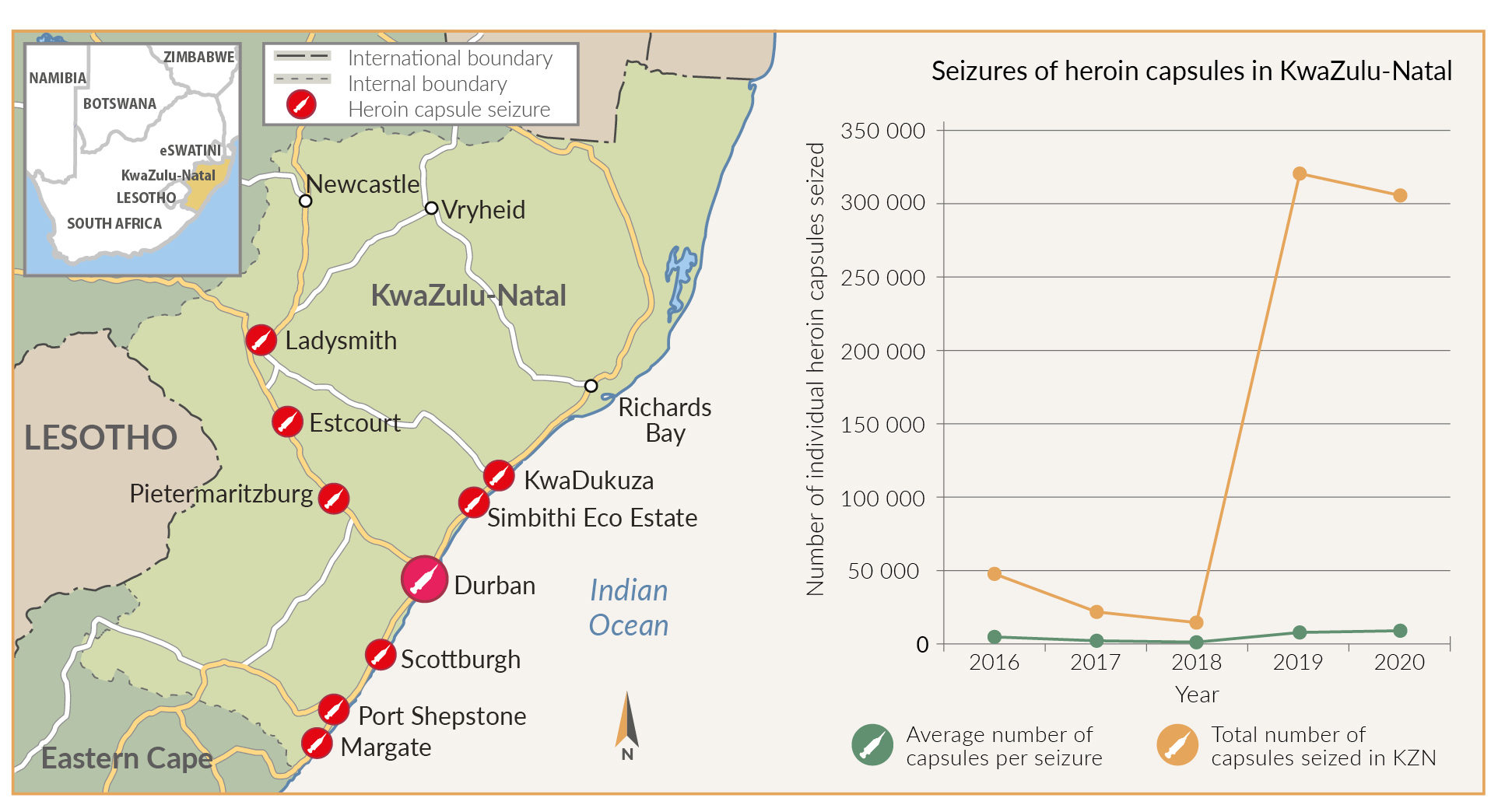

In September 2020, members of the Hawks (South Africa’s organised crime police unit) uncovered more than 170,000 heroin capsules at an upmarket residential estate about 50km north of Durban. The capsules were part of a haul that also included thousands of tablets of Mandrax and methaqualone (a precursor for manufacturing Mandrax), as well as other large volumes of heroin.

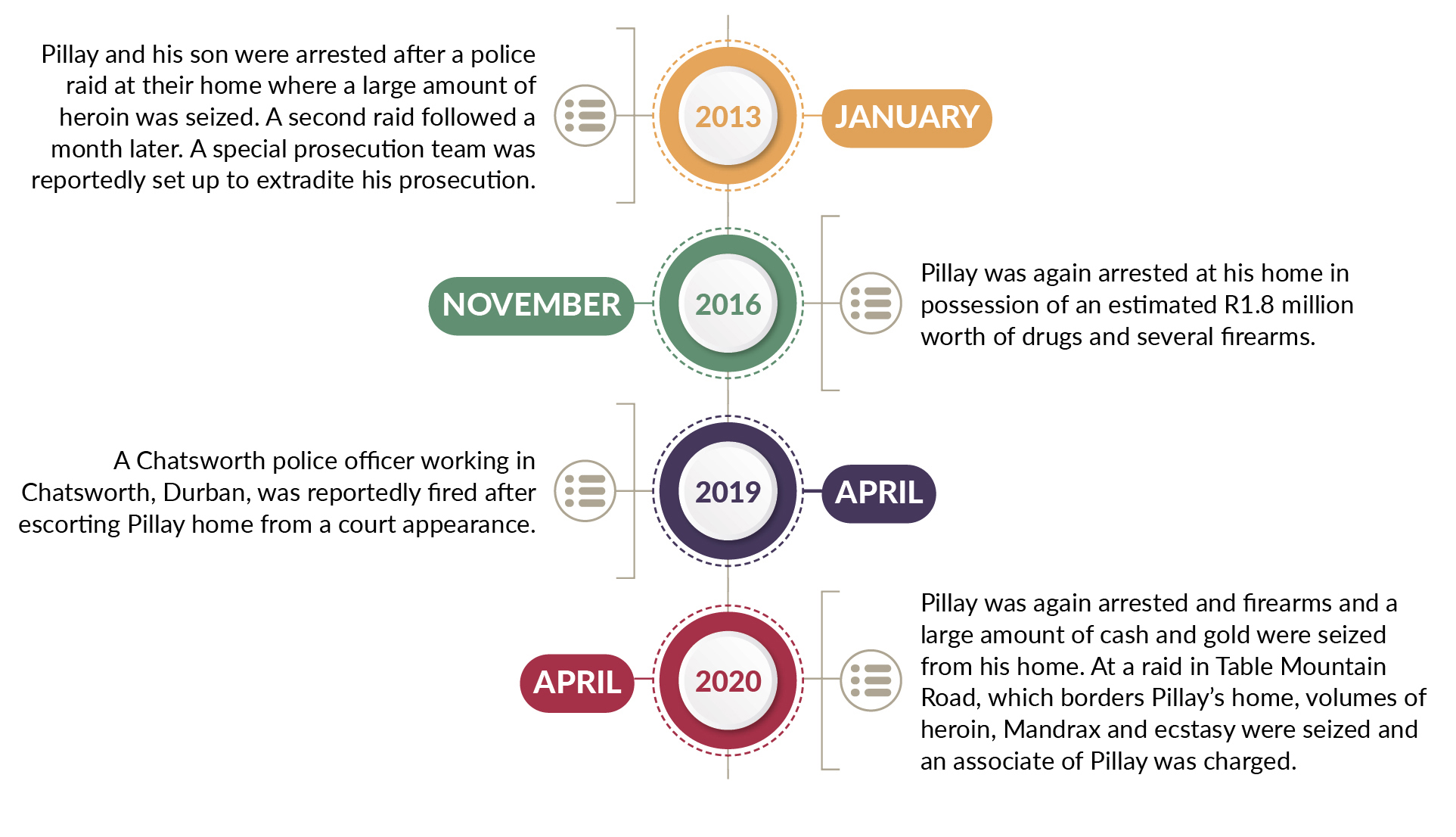

This raid was one of the largest hauls of heroin capsules in KwaZulu-Natal. According to our analysis of drug seizures reported by the South African Police Services, there have been 13 seizure incidents in KwaZulu-Natal since January 2016, which have each led to the seizure of more than 10,000 capsules, and a much larger number of smaller incidents.

In recent years, raids have also discovered laboratory equipment designed to automate the high-speed manufacture of thousands of heroin capsules. One such raid in Springfield Park in Durban in March 2019 revealed capsule-pressing machinery and thousands of empty capsules, with police estimating that they believed 10,000 capsules containing heroin were being manufactured per day.

![]()

Samples of heroin from locations in South Africa. The central image shows a heroin capsule, pictured in Durban. The left and right images, collected in Cape Town and Port Elizabeth respectively, show plastic-wrapped heroin. This is how heroin is generally packaged for consumption in South Africa: capsules are a phenomenon that is unique to Durban. (Source: GI-TOC)

Since January 2016, more than 710,000 individual capsules containing heroin have been seized in South Africa, according to our analysis. That a single laboratory could produce up to 10,000 capsules per day goes some way to illustrate that the 710,000 reported seized by police are merely the tip of a much larger iceberg.

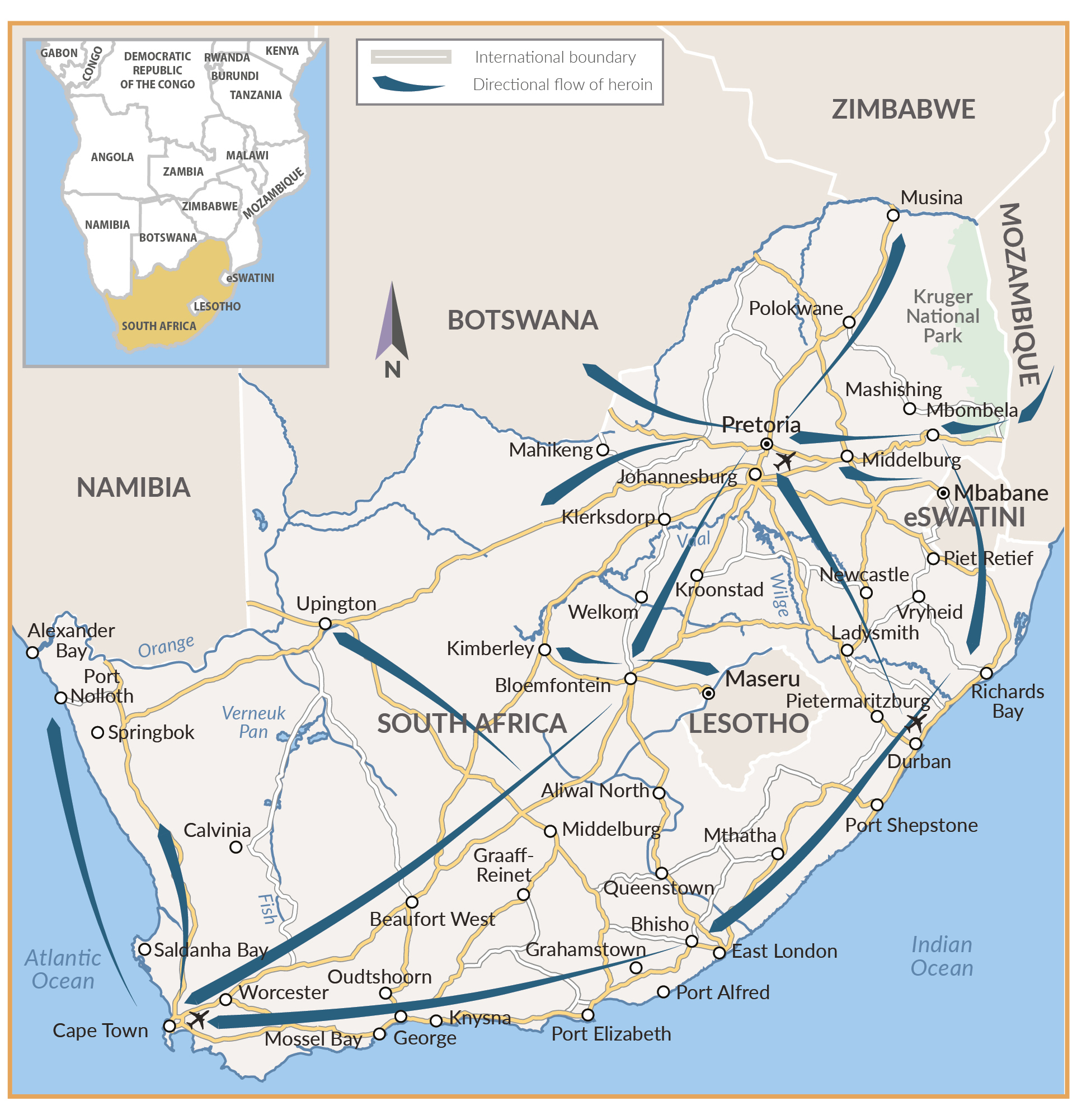

However, the data is useful in illustrating the geographical concentration of these capsules. During this analysis, no reports were noted of heroin capsules being seized in South Africa outside of KwaZulu-Natal, and seizures have been overwhelmingly concentrated in Durban. Other seizures were made in surrounding towns near Durban (such as Pietermaritzburg) – all along major roads leading out of the city within a 200km radius.

This corresponds to the findings of our 2020 study that surveyed illicit drug prices and market dynamics across eastern and southern Africa, including 15 drug market sites in South Africa. Metrics measured included a comparison of the retail packaging of heroin samples, with capsulised heroin reported only in Durban and Pietermaritzburg. In other samples collected from Durban and around the country, heroin is more commonly plastic-wrapped and tied – a form of packaging known as a “twist” or “twister”, among other names.

Examples of heroin in capsule form are also rare outside of South Africa: our research team is aware of only two other examples. During our research in 2020, capsules were reported by people who use drugs (PWUD) in Busia, a border town that straddles the Uganda–Kenya boundary. In an earlier, seemingly isolated incident in January 2016, 4,200 capsules of heroin were seized from a woman who was travelling from the Democratic Republic of Congo and attempting to enter South Africa via Zimbabwe.

![]()

Figure showing a timeline of Incidents involving ‘Teddy Mafia’, suspected leader of a drug trafficking network in Durban. (Source: GI-TOC)

The capsules in Busia, in particular, raise questions because of the seizure’s geographic isolation. In interviews, sex workers and PWUD in Busia reported that the capsules were mainly provided by truck drivers. It is possible that the easily disguised pharmaceutical packaging may be an advantage for these drivers when travelling across borders. There was no evidence to suggest that Busia was either the source or the ultimate destination market for these capsules. This leaves questions open as to where these capsules originally came from, where they are ultimately sold, and why they are appearing on the Kenya–Uganda border, so far from the only other recorded location for capsules, in Durban.

In both cases, the capsules containing heroin do not appear similar to those being produced in KwaZulu-Natal, with the drug being re-sealed into pharmaceutical-style blister packs in order to resemble regular medical products. By contrast, the capsules sold in Durban are stored as loose capsules.

The evidence suggests that capsules have come to be widely used only in recent years in Durban’s heroin market. One Durban-based police officer speaking to GI-TOC in 2019 described how, in the early 2000s when the heroin market was in its infancy, heroin was largely sold in plastic-wrapped “chalk sticks” known as dongas. After this, heroin began to be packaged in straws, which involved a lot of manual labour to prepare. Finally, capsules became more common. Seizure data supports this narrative, as the number of capsules seized has increased exponentially from fewer than 50,000 annually before 2018 to more than 300,000 in 2019 and 2020.

The shift towards capsules has brought about a revolution in efficiency, creating an assembly-line style of production that outstrips other methods. In addition, studying retail packaging can provide interesting information about forms of drug consumption and supply routes.

For example, the fact that no samples have been reported in our South Africa pricing surveys outside of KwaZulu-Natal – either by police or by PWUD – may suggest that the distribution networks that actually transfer the heroin from bulk into capsules cater only to a local consumer population. Since South Africa’s large and growing heroin market is nationwide, in particular in Johannesburg and Cape Town, one might expect some examples from other areas if the capsules were being produced by a network that distributed its wares further afield. However, there is a possibility that examples of capsule heroin may be being overlooked. After all, in capsule form the drug can more easily be disguised as an innocuous medicine, passing under the radar of police and researchers alike.

![]()

The number of heroin capsule seizures in KwaZulu-Natal has risen sharply since 2018. Seizures of these capsules are highly concentrated in and around Durban, and no seizures have been reported outside of the province. (Source: Seizures reported by the South African Police Services)

In an interview, one Durban police officer argued that dealers had shifted to capsules because consumption in the area had increased: capsules allow dealers to produce a larger quantity more efficiently. While this is a logical argument – capsule production is undeniably more efficient – this in turn raises the question: why has a similar technological revolution not been seen in other parts of South Africa, where heroin consumption is rising as fast as in Durban? Why has the technical expertise seemingly not been passed to networks in other cities, especially when links between Durban drug gangs and those in Cape Town have been previously documented? The concentration around Durban raises many questions for future analysis.

A turbulent drug market: the example of ‘Teddy Mafia’

The trend towards heroin capsules has emerged at the same time as Durban’s drug market at large has become more volatile. As our research into the political economy of urban drug markets across the region has found, there are a few key factors in understanding the drugs landscape in Durban. All these factors are exemplified in the story of Teddy Mafia (real name Yaganathan Pillay), a well-known local drug kingpin whose assassination on 4 January this year – and the subsequent mob execution of his killers – rocked Durban.

Drug dealers in Durban often operate with a very high public profile, enabled by a climate of impunity that derives from police corruption. Teddy Mafia was a case in point. Sources in crime intelligence and civil society in Durban described him as a “notorious” dealer in Durban for many years who managed to evade prosecution, despite overwhelming evidence. He was arrested in January 2013 alongside his son after a police raid at their home. A large amount of heroin was seized in the raid, which was hailed as a “major breakthrough” by police at the time and led to the creation of a special prosecution team in order to expedite his prosecution. In November 2016, Pillay was arrested with drugs worth an estimated R1.8-million ($125,000) and several firearms. Finally, in April 2020, his arrest at his Taurus Road home accompanied the seizure of several firearms, while a suspected associate was arrested in possession of a significant volume of drugs nearby.

Despite these multiple major incidents and the investment of police resources, Teddy Mafia was never convicted of a drug-related offence. In the aftermath of his shooting, South African Police Minister Bheki Cele asked police why Pillay, as a “known drug dealer”, was never successfully prosecuted.

Sources say that this was thanks to law-enforcement officers on his payroll. “He had many magistrates and senior police guys in his pocket so he could move around and avoid prosecution as he was powerful that way,” said a 45-year-old gang member from Sydenham.

![]()

Figure showing a map of distribution flows of heroin in South Africa. (Source: GI-TOC)

In interviews, Durban police officers have given scathing assessments of the corruption situation. One police officer in a leadership role argued that Durban would not be home to powerful and well-known dealers without police tip-offs and corrupt support. Another argued that the pervasive corruption made it dangerous and difficult to do investigative work into the drug trade: “Durban is so corrupt, you don’t know who to trust,” he said.

Speaking to the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC) in May 2019, Sam Pillay, a long-standing community activist, expressed frustration at trying to work with the police: “Since the early days, we knew the dealers, we knew the trade. We knew their pawn shops. We knew the names of the cops who arrived to collect tax. And we supplied that information to the relevant bodies in law enforcement, but there was no will to shut them down. Some of them do get arrested, but there are no convictions.”

The community also offers a layer of protection for drug dealers who provide charitable donations to locals in order to win support, presenting themselves as “Robin Hood” figures. Again, Teddy Mafia was no exception. A source in the Crime Intelligence Division said that Pillay was “protected by the community because he supports them financially”. A former police officer in Chatsworth – Pillay’s local area – said “he [Pillay] had big pockets, so many people loved him and would easily fall on a sword for him… you know how these gang bosses are? They anoint their communities with false charity while they inject those very communities with poisonous drugs that get these youngsters hooked and destroy their lives.”

When a GI-TOC research team visited Chatsworth in 2019, a queue of people was outside Pillay’s home, apparently waiting to receive food distributed from his driveway or to ask for loans. As we drove past, men in nearby hostels blew whistles, which community activists said is a system used to alert drug dealers to a potential police raid. At one of Pillay’s previous court appearances, supporters reportedly wore T-shirts with the words “The people’s champion” printed on them in support.

But Durban’s drug market has grown more violent in recent months, with what has been described as a “turf war” between rival dealers leading to a series of assassinations. This included hits on several members of Teddy Mafia’s family. Police in the area have also reported that gang dynamics in Durban have been shifting, with local gangs developing into larger criminal enterprises and becoming more violent in their fight for territory. Criminal figures in Durban have reportedly hired hitmen from Cape Town to carry out assassinations of rivals.

![]()

Figure showing a timeline of assassinations and attempted assassinations suspected of being linked to the drug market in Durban, 2019–2021. (Source: GI-TOC)

These two key trends – rising violent competition and community support for drug kingpins – came together around the events of 4 January 2021, when Pillay was shot in his home in Chatsworth. The two shooters, who were reportedly known to Pillay – one reporter on the scene later that day reported that these men had previously worked for Pillay – came to the house and were allowed past Pillay’s strict armed security. According to a source working in crime intelligence in Durban, the alleged purpose of the meeting was to sell unlicensed firearms to Pillay. However, the source went on, it was, in reality, an assassination ordered by a rival dealer in Chatsworth, against whom Pillay had been waging war.

The men shot Pillay and fled, only to be caught by a mob that had assembled outside the house. They were then reportedly shot, and footage shared widely on social media shows the bodies being beheaded and then burned in view of an assembled crowd of hundreds. As police attempted to come to the scene, they were reportedly driven off by community members shooting and throwing stones and were unable to access the scene for several hours. It seems that Teddy Mafia’s standing in his community spurred the vicious treatment of his attackers.

Unanswered questions over the rise in the use of heroin capsules

As shown by the career of Teddy Mafia, the phenomenon of heroin capsules – the development of a resource-intensive, more efficient mode of drug distribution – has taken place under a certain set of circumstances where police are highly compromised, drug networks can operate confidently with impunity (and often with community support) and the rising value of the drugs market (thanks to growing consumption) is spurring violence as groups compete for control. Residents of Shallcross, Durban, have voiced their fears that Teddy Mafia’s assassination will lead to further drug market violence.

But how to interpret this phenomenon is still a very open debate. On one hand, it could be argued that investments in laboratory-style equipment to improve heroin production efficiency demonstrate that drug networks in Durban have been emboldened, and are not concerned that sourcing pharmaceutical equipment could raise suspicion. On the other, in a context where corruption is rife and drugs networks are well protected, what is the advantage of concealing heroin in capsule form? Further investigation into the unique characteristics of the Durban drugs market may seek to answer these questions. DM