The Cult of Professor Carroll Quigley – Bill Clinton’s professor

[A fascinating article. Jan]

The Quigley Cult

What do President Bill Clinton and the military have in common?

They both revere the weird theories of the late Carroll Quigley.

By Scott McLamee

During his second semester at Georgetown University, Bill Clinton did a bold thing. He skipped classes. More to the point, he missed four sessions of Development of Civilization, a yearlong course for students entering the School for Foreign Service, taught by Professor Carroll Quigley.

Quigley was something of a legend, and not just at the university. He lectured at the Brookings Institution and at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. He wrote for the Washington Post and the Star, the now-defunct D.C. daily newspaper. And the talks he gave at the State Department on Africa and France were worked up into articles for the magazine Current History, where Quigley served on the editorial board. He was a consultant to the House Committee on Astronautics and Space Exploration and had some connection with the birth of NASA. His work even caught the attention of Herman Kahn, the consummate policy wonk of the late ’50s and early ‘60s, who was then thinking deep thoughts on thermonuclear war, and scaring people to death in the process.

(Future) President Bill Clinton

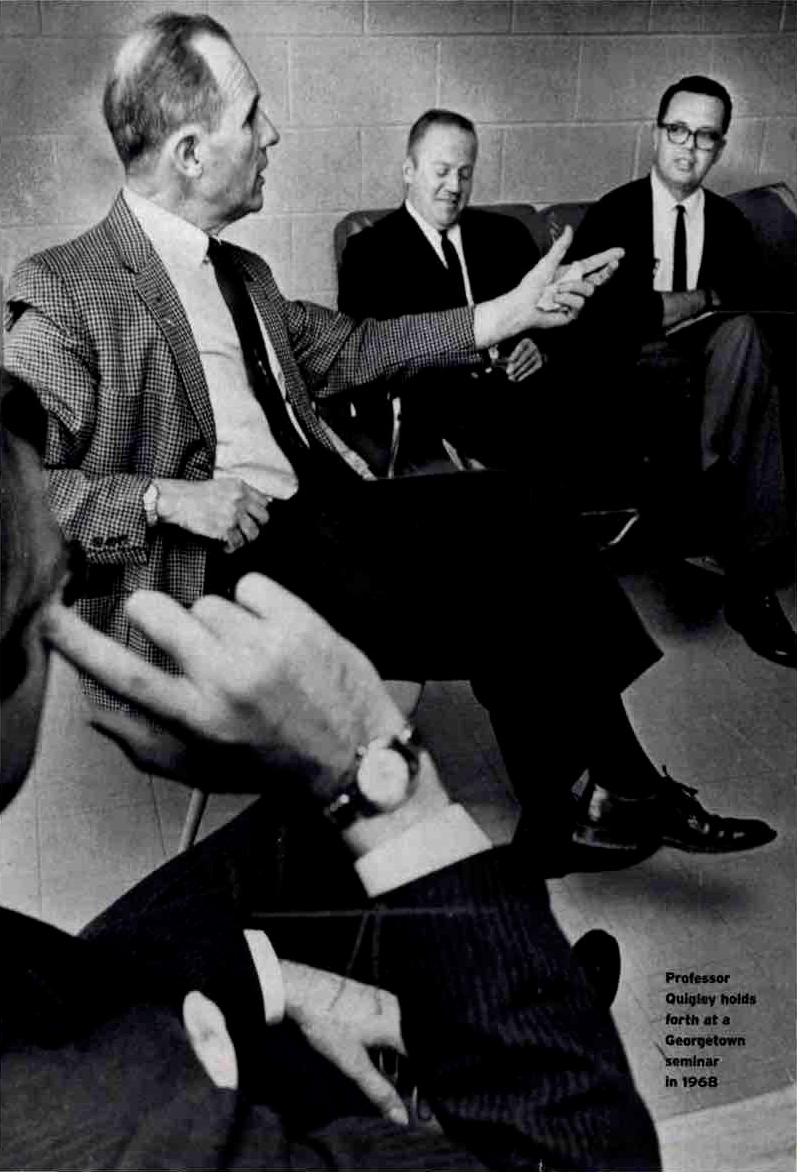

In the classroom, Professor Quigley himself inspired a kind of dread. His lectures were dramatic performances, and his exams terrified generations of freshmen at Georgetown. Nearly half of the 176 students who enrolled alongside Bill Clinton scored a D or below for the fall 1964 semester. In Professor Quigley’s hands, the study of Western Civilization was a demanding activity for all parties involved. “I’m in the business of teaching people how to think,” Quigley liked to say, “of training executives and not clerks.”

But it was also part of the Quigley legend — the substance of generations of undergraduate rumor — that you could survive his course by conscientiously learning and reciting back his ideas. Of course, university students have been saying that kind of thing about their professors for about a thousand years, sometimes justly, sometimes not. But Quigley had indeed worked out his own theory of history, with its own jargon, and this was worth knowing. When an exam question asked, “How does a civilization decline and fall?” — as the first exam for the fall 1964 semester did — it would have been prudent to form one’s answer by invoking the Quigleyan principle of “the institutionalization of the instrument.”

“Professor Quigley holds forth at a Georgetown seminar in 1968”

Bill Clinton, it seems, mastered basic Quigleyism in rapid order. Friends recall that he would stay behind after class with a clutch of students who threw questions at the professor. The scores in the professor’s grade book for the 1964 – 65 school year (preserved, like the rest of Quigley’s papers, at the Georgetown University library) form a row of figures hovering steadily in the B range for Clinton — save for a solitary and conspicuous D, probably from a test early that semester designed to concentrate students’ attention through pain and fear. Overall, Clinton got a B for both parts of the course, and the sharp rise of absences in the second semester (he missed only one class in the fall) might indicate a certain degree of confidence in grasping the art of testmanship under the Quigley regime.

In books on the President that have appeared since 1992, discussions of Quigley are scarce and always brief. They seldom note more than his transit across the young president-to-be’s path. But Clinton himself often recalled the professor in his speeches. (Quigley died in the first days of 1977 — too soon to see his former student elected to office). Clinton mentioned him in his first inaugural speech as governor of Arkansas. He spoke of Quigley at Georgetown University in 1991, while launching his presidential bid. And so it should have been of little surprise that in accepting the presidential nomination at the Democratic National Convention in 1992, Clinton once again invoked the professor: “As a teenager, I heard John Kennedy’s summons to citizenship. And then, as a student at Georgetown, I heard that call clarified by a professor I had, named Carroll Quigley, who said that America was the greatest nation in history because our people have always believed in two great ideas: That tomorrow can be better than today and that each of us has a personal, moral responsibility to make it so.”