Photos: UnitedKikedom: Wonderful Diversity: Remembering the 2001 English Race Riots

[I do enjoy the term one of my supporters uses: UK = UnitedKikedom! It's so true. Britain is the home of the Jew! And the king of the Jews lives there … Rothschild. Jan]

“Crime in Oldham had reached ‘record levels’ with a massive increase (to 60 percent of all incidents) in violent attacks on whites.”

David Waddington, Policing Public Disorder[1]

The racialist is bound to an instinctive love-hate relationship with the race riot. On the one hand, racial violence is a cause for sorrow and disgust. It represents the fullest expression of the violent disintegration of prior ethnic homogeneity. On the other hand, the race riot is a powerful vindication and an unveiling. It’s an honest illustration of ethnic truths that are always present but often covered up by a variety of bribes, propaganda devices, excuses, and false or temporary panaceas. For the racialist, ethnic conflict is a predictable, inevitable, and violent eruption of reality into the dreamlike fantasy of multiculturalism. The race riot, with its explosive unraveling of communal grudges and hostilities, can be postponed, reinterpreted, and badly explained by those in power, but, for the racialist, it cannot ever be permanently avoided; its potential is etched into the very fabric of the multicultural project.

This summer marks the twentieth anniversary of a sequence of race riots in northern England that had a transformative effect on my worldview, and continues to exert a significant influence on how I see the world. More than Jewish historical fairy tales or Islamic terrorism, this was the primary moment of my political awakening. It was the first time I heard about “no-go” areas dominated by foreign ethnic groups, the first time I learned about the activities of the British National Party, and the first time I gained an understanding of the fact that we are only ever a simple shift in context and circumstances away from explicit racial enmity. I learned during that summer two decades ago that, ultimately, it doesn’t matter how tolerant you think you are or desire to be — what matters more is how the other side will see you when push comes to shove. And whether or not you subscribe to Social Darwinism in its finer points, it is a simple fact of human history that push always comes to shove. Violence between groups over resources has always occurred, and will never cease.

Such was the painful lesson learned by 76-year-old veteran Walter Chamberlain who, in April 2001, was walking home from a rugby match through a predominantly South Asian area of Oldham when he was set upon by a group of Pakistanis. Having committed the grievous error of deciding to walk through “their” neighborhood, Chamberlain was beaten senseless, and suffered several broken facial bones. Four decades of ethnic tension, dating to the arrival of the first significant waves of Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Indian migrants in Oldham, had bubbled over. Once Chamberlain’s battered face appeared on the front pages of several national newspapers (I vividly recall seeing it while purchasing a copy of Combat, a now defunct UK martial arts magazine), a White backlash seemed inevitable.

The attack on Walter Chamberlain was merely a final straw. Racial violence against Whites had been escalating in the South Asian enclaves of northern England for years. Prior to the attack on Chamberlain, Greater Manchester Police’s “Q Division (Oldham)” had issued a number of warnings about the nature of ethnic crime and violence in the town. The Chief Superintendent, for example, wrote in one report that

There’s evidence that [Asian male youths] are trying to create exclusive areas for themselves. Anyone seems to be a target if they are white. It is a growing polarisation between some sections of the Asian youth and white youth on the grounds of race, manifesting itself in violence, predominantly Asian.[2]

Four months before the attack on Chamberlain, Greater Manchester Police released a report showing that “62 per cent of racial incidents were Asian on white. A special report for the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester emphasised that these were part of an ongoing trend involving primarily Pakistani and Bangladeshi teenagers.”[3] Academics have since attributed the later race riots in part to honest media portrayals of these reports and incidents, which acted to stimulate a sense of White cohesion and victimisation. The Oldham Chronicle, for example, had been brutally honest in its reports during the late 1990s, leading with a number of headlines such as “Racist Attacks By Asian Gangs,” (March 17 1998), and “HUGE RISE IN RACE ATTACKS ON WHITE MEN” (January 31 2001). The police, the local media, and the Whites of northern England have since come in for severe criticism by the foremost academic apologist for Pakistani crime, who insists, without evidence, that South Asians were actually the most victimised population prior to the riots but had low trust in the police and therefore didn’t report crimes against them.[4] This apologist is the sociologist Professor Larry Ray (University of Kent), whose motivations, considered in light of his past Presidency of the British Association for Jewish Studies, require no further discussion for the well-informed readers of this website.

Larry Ray: Jewish Apologist for Pakistani violence against Whites

The increase in violence in Oldham, and similar trends in Burnley and Bradford, caught the attention of both the National Front and the British National Party, both of which astutely flooded these towns with pamphlets, some bearing the battered visage of Walter Chamberlain. In combination with honest local media reporting, these groups helped to further heighten White cohesion, solidarity, and ethnocentrism, with the National Front even promising to march through the Asian-dominated “no-go” areas in a White “show of strength.” The march was quickly banned by the Home Office, but White ethnocentrism in these towns was obviously on the rise. Once it reached adequate levels, it was only a matter of time before opposing racial factions clashed on a larger scale. The Pakistanis, for their part, had started daubing walls on their streets with the slogan “Whites Keep Out.”[5]

The Riots

As in most cases of ethnic conflict, the initial flashpoint for mass violence was relatively banal but escalated quickly. A month after the attack on Walter Chamberlain, a White youth spotted two Pakistani brothers walking past a Fish and Chips shop, and threw a brick at them, striking one on the leg. The two Pakistanis followed the youth to a nearby house, and word was quickly spread to other Pakistanis in the area. In a short period of time, more than a dozen Pakistanis had gathered outside the house seeking violent retribution from the lone White perpetrator. They then kicked in the front door. The woman who owned the house called both the police and her 25-year-old brother, who was then socialising in a nearby pub with members of the British National Party and a Far Right paramilitary organisation known as Combat 18. The group made their way from the pub to the scene of disturbance in three taxis, and set about responding to Pakistani intimidation by smashing the windows of South Asian residences and businesses. The police then arrived, arresting 10 members of the White grouping, and two Pakistanis who’d been involved in attacking the house. Within an hour, a 500-strong crowd of Pakistanis formed street barricades and began throwing petrol bombs and other missiles at police. Between 10pm and 5am of the first episode of major violence, four pubs were almost destroyed along with the offices of the Oldham Chronicle (presumably for its reporting of Pakistani crime), and 32 police vehicles were damaged. Scenes of chaos from Oldham’s streets were broadcast around the world.

A month after the Oldham riot, trouble erupted in Burnley. The town had a growing population of young Pakistani males, who formed criminal cliques that acted as rivals to White criminal gangs as well as assaulting or robbing non-criminal Whites. As well as absorbing the tensions emanating from Oldham, Burnley had its own problems. The town had an “Equal Opportunities Co-ordinator” who was accused of helping to provide preferential council investment to South Asian-occupied areas. The controversy led to a spike in British National Party representation on the local council (to 21%), as well as to calls for the abolition of the role of Equal Opportunities Co-ordinator (the town’s Race Equality Council had also recently been disbanded). The final spark arrived in June 2021, when there was an altercation between South Asian and White criminals, which resulted in a Pakistani being struck on the head with a hammer. False rumors that the Pakistani was dead began circulating in the South Asian community, and a mob of armed males gathered at, and subsequently attacked, the Duke of York pub, which was regarded as being frequented by the White element.

The following day, the pub’s landlord closed the establishment and informed arriving customers what had happened. Large numbers of Whites, including around 60 youths, who had no involvement in the events of the preceding days, were reported by police at the time as having adopted “something of a siege mentality,” and began chanting racial slogans at nearby Pakistani taxi drivers. Using taxi radios, much of the town’s young Pakistani male population was mobilised into action and was instructed to attack Whites gathered at the pub. This Pakistani mob, later estimated by police as numbering at least 300, armed themselves with machetes and clubs and made their way to the Duke of York. Before they arrived, the 60 White youths divided into two groups. One of these groups was intercepted by police, who then inexplicably steered them into the path of the armed 300 Pakistanis. The police then hastily formed a barrier between the two ethnic groups, with each then turning their violent intentions towards rival residences and businesses on their side of the police barrier. As with Oldham, these scenes were broadcast around the world.

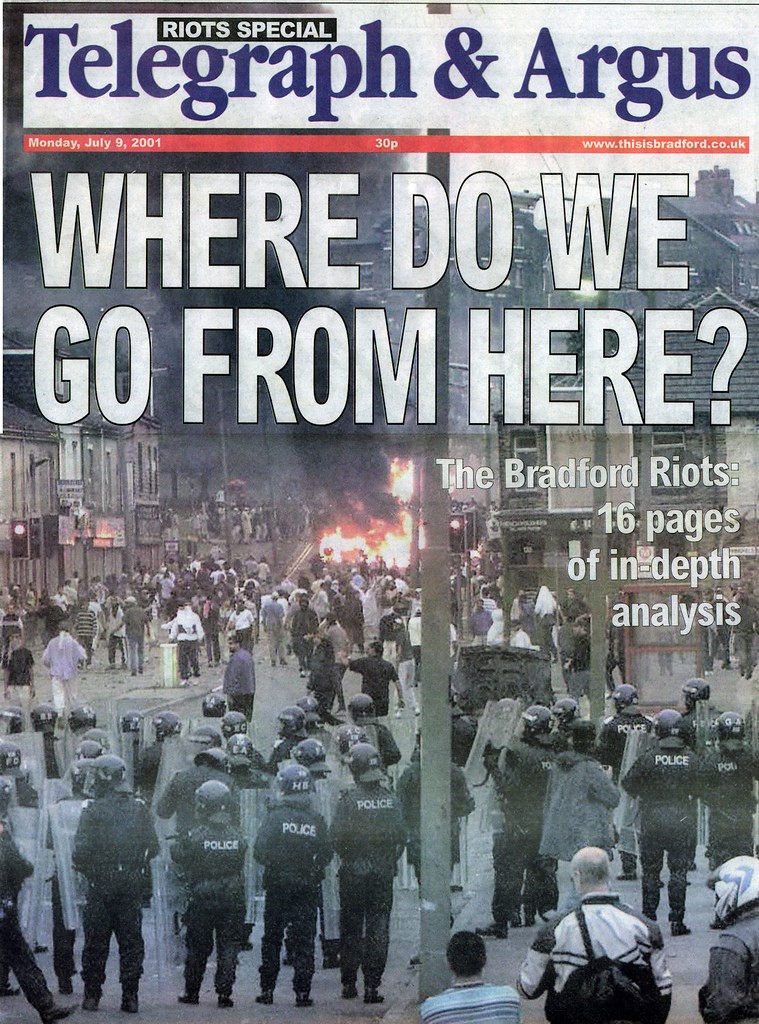

A few weeks after the ethnic chaos in Burnley, it was Bradford’s turn to combust.[6] In 2001, Bradford had the second largest population of South Asians of any UK city, with approximately 68,000 Pakistanis, 12,500 Indians, 5,000 Bangladeshis and 3,000 other Asians. The White demographic had declined to 78% of the total population, and the town was host to many of the same issues in Oldham and Burnley: decades of tense segregation; a culture of criminality among young South Asian males; and a sense that local government resources were being invested in South Asian communities at the expense of the working-class native population. It should also be added that the town had already witnessed large-scale race riots in the form of the 1995 Manningham Riot. As in the other towns, the National Front and the British National Party supplemented growing White racial consciousness in the area (already prompted by press coverage of South Asian criminality) by engaging in intensive pamphleting, making advances in local government elections, arranging marches, and hosting meetings. When the spark finally arrived, Bradford exploded with one of the most violent of all the race riots that occurred in 2001, resulting in more than 300 injured police officers, 200 jail sentences totaling 604 years, and an estimated £7 million in property damage.

In Bradford, the spark was provided on July 7 by the “Anti-Nazi League,” who declared their intention to prevent the National Front from marching in the city center. The group comprised a small White leftist element and several hundred South Asians. The protest did little more than push National Front/BNP supporters to the fringes of the city, where clashes with South Asians were in fact more likely to take place out of sight of police. Around 3pm, rumors began circulating among the Antifa/South Asian element that members of the National Front were socialising at a nearby pub. A faction set off in search of the pub and, during an attempted attack on National Front members a Pakistani was stabbed. Shortly after this point, the smaller White leftist element departed the city center, leaving a rump of several hundred Asians who soon began throwing missiles at watching police, looting several shops, and smashing windows. Around 5pm, two White men were stabbed by a group of South Asians on Thornton Road, and a group of 60–70 South Asians began resisting police attempts to clear the city center by throwing petrol bombs. The crowd was only dispersed following several police charges on horseback, but during the chaotic retreat of the South Asians, Mohammed Ilyas, a 48-year-old Pakistani businessman and father of six, firebombed the Manningham Labour Club, a White-frequented recreational center, while 23 men and women were still inside. Those inside managed to survive by taking refuge in the building’s cellar. Ilyas was subsequently caught and sentenced to 12 years in prison.

The following night, around a hundred White males gathered near Bradford city center seeking retribution, before setting off in search of South Asian-owned businesses in the Ravenscliffe and Holmewood areas. Following mass damage to Pakistani businesses, vehicles, and property, the police flooded the area with almost 1,000 officers, which brought an end to the riots of July 8. The following night, however, these events were repeated. Police again flooded the streets of Bradford, this time bringing a lasting but uneasy peace.

Legacy

Did ethnic relations in these towns improve? Can we assume that, since the riots have not been repeated, somehow multiculturalism now “works” in these areas? As mentioned at the outset of this essay, as a racialist I believe that ethnic conflict will be the natural state of affairs within multiculturalism, and that where it is not obviously present that is because it has been covered up by a variety of bribes, propaganda devices, excuses, and false or temporary panaceas. In the aftermath of the riots, the government said much about fostering “inclusion,” about “breaking down barriers,” about “encouraging understanding,” and about improving the material lives of the neglected Whites of northern England — words entirely without meaning or honest intent. Five years after the riots, one resident of Burnley told the BBC, “Nothing’s changed, it may have got worse. … The poor white areas still do not get any government help. Duke Bar is a no-go area after dark. So much for all the Government talk about helping Burnley.” Within several years of the riots, Oldham and Bradford evolved into the largest epicenters for the South Asian sex trafficking of hundreds of White girls. Today, the White population has Bradford declined to 63%, while Oldham and Burnley have experienced slower rates of White demographic displacement. Two decades after the riots, Whites and South Asians continue to live in a state of tension.

Since South Asian expansion and criminality hasn’t disappeared, the real question is what happened to the capacity for White reaction. It’s clear in this regard that, rather than deal directly with the problems inherent in multiculturalism, the government pursued a policy of neutering White anger and ethnocentrism as the best method for preventing further riots. Since White solidarity leading up to the riots was perceived as originating with press reports and the activities of the BNP and the National Front, these were two obvious starting points for preventative measures. Criticism of the honest reporting of the Oldham Chronicle, exemplified in the work of Professor Ray, culminated 11 years later in a government report issued by Lord Brian Leveson, who describes himself as a “devout Jew.” The report, known as the Leveson Report, revolutionised press standards by condemning “careless or reckless reporting” that includes “discriminatory, sensational or unbalanced reporting in relation to ethnic minorities.” In other words, referring to such things as “Asian crime” or “Attacks on Whites” in news headlines became a thing of the past, and so White perceptions of their victimisation and the nature of ethnic crime were disrupted and stifled.

Political White Nationalism in England also came under sustained attack from various quarters. In 2004, elements of the media contrived to undermine the BNP and “expose” its racism to the public, eventually resulting in the Channel 4 documentary The Secret Agent. The documentary involves little more than an undercover journalist presenting secretly recorded footage of low-level BNP members uttering some controversial sentiments while under the influence of alcohol. The risible footage nevertheless led to an attempt to prosecute both Nick Griffin and Mark Collett for incitement to racial hatred, both of whom were found not guilty at trial. Continued harassment and disruption of the BNP continued into 2009, however, when the Equality and Human Rights Commission undertook court proceedings to force the BNP to accept non-White members. Finally, there was a sustained push to present UKIP’s civic nationalism as a more respectable “protest vote” against the established parties. The BNP was never able to recover.

White anger and ethnocentrism were also suppressed through a tightening of the law. Two years after the riots the government passed the Criminal Justice Act 2003, sections 145 and 146 of which granted courts the power to increase sentences for any crime in which racial or religious motivations were suspected. Going further even than the idea of a “hate crime,” the legislation made it clear that even perceived “hostility” to the injured party would be sufficient to come under its terms. Placed in the context of an ethnically defined riot, for example, a White youth caught breaking a window would now attract a significantly higher sentence than the normal punishment handed down for criminal damage.

Muzzling the media, disrupting White ethnic politics, and tougher legal punishments for White protest — this is how the government temporarily solved the problem of race riots in England. I say “temporarily” because it’s only a matter of time before even these measures become insufficient to cover up the simmering tensions built into multiculturalism. A further dramatic shift in interethnic relations is an inevitability, and will probably involve the reaching of certain demographic tipping points or a dive in the economy leading to scarce resources. The final spark will be caused by something banal. Instinct will kick in. Tribes will form. People can be awakened by the innocuous as well as the dramatic; the distant as well as the near. For me it began twenty years ago, with a brick thrown in Oldham.