Photos: ART: IMPORTANT: Ugly, Hateful Hag Feminism: Worship of demented European woman beheading White males – My Comments

[Here is an utterly brilliant article from Occidental Observer. You have to see this to believe it. It is beyond belief the sheer hatred of this hideous European woman. I was very taken by the extremely beautiful artwork of the French lady artist … a truly talented, lovely white woman. Her self portrait is so lovely. Such talent. Also such femininity. White women used to be amazing. European society was fantastic. And now these miserable feminist, male-hating, hags and degenerates, led by Jews are making women worship a degenerate male-hating female painted who painted the most disgusting artwork I have ever seen. I never knew such male hating rubbish came out of Europe. Modern Feminists are led down the path to HATE WHITE MEN. This is very sick. Very. We need decent relations established between the sexes. Jan]

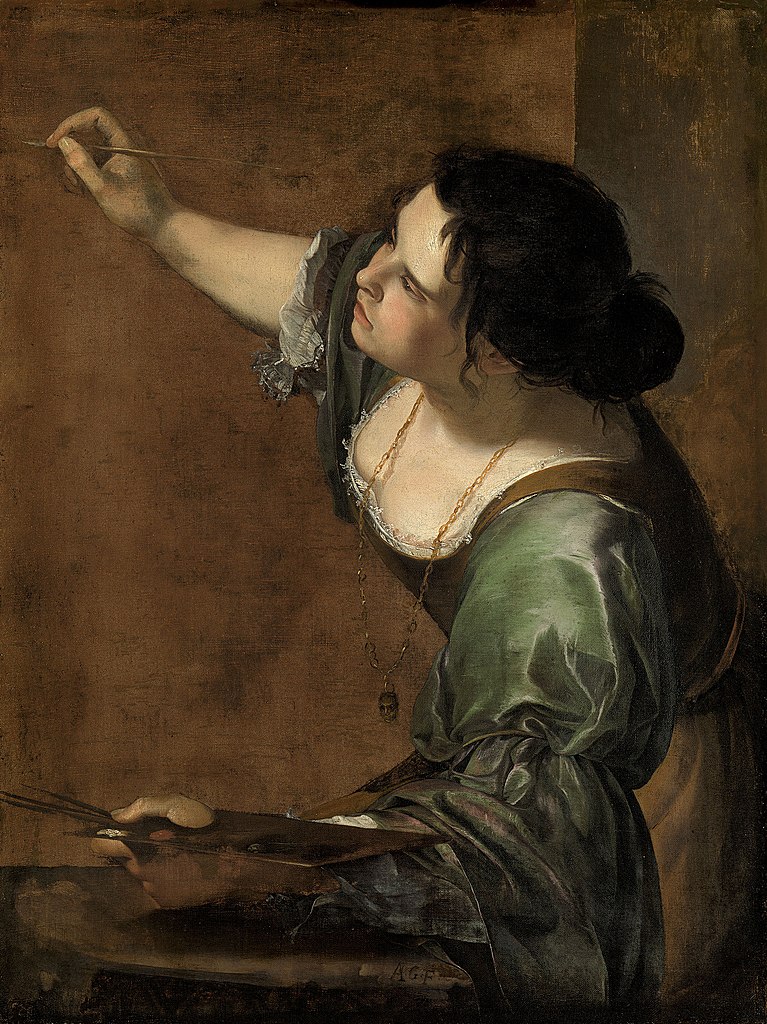

“She was a genius,” says the Guardian. She was a “uniquely gifted artist who should be considered among the all-time greatest painters,” says the BBC. I say, no, she was not. The Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c.1656) was not a genius, was not uniquely gifted and should definitely not be considered a great painter. But don’t take my word for it — see for yourself. Here is one of her most famous and extravagantly praised paintings:

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (c. 1640), Artemisia Gentileschi

Given the title of Gentileschi’s self-portrait, you can’t fault her ambition and egocentricity. But you can fault her perspective, her composition, her colouring, her grasp of her own anatomy, and her ability to represent fabric, flesh, and hair. Here for comparison is a self-portrait by a genuinely gifted female artist, the French Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun (1755–1842):

Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat (1782), Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun

Vigée-Le Brun represents herself as attractive and enjoying both life and being a woman. Feminists don’t want women to be attractive and happy like that. They want women to be unhappy, angry and militant. That’s one big reason they prefer the untalented Gentileschi to the highly talented Vigée-Le Brun. I don’t think Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting even rises to the level of bad art. The words that come most naturally to my lips are “bloody awful.” The first time I saw the painting in a book of art history, I wondered whether its inclusion was a joke or mistake. How could any art-historian or critic take that mess seriously?

The siren-song of solipsism

Very easily, it became apparent. And very prudently too. Anyone at the Guardian, BBC or other leftist institution who spoke the truth about Artemisia Gentileschi’s sometimes execrable art would be in serious trouble. If Gentileschi had been a man and painted to the same low standard, she would quite rightly have been forgotten long ago. But she was a woman and a “rape-survivor,” so feminists in the 1970s decided to create a cult around her. By worshipping her, they were really worshipping themselves, because I think some or perhaps most feminists don’t see other women as individuals or even as human beings in their own right. Instead, those feminists see other women as reflections of themselves or as counters in the feminist struggle for power and self-assertion.

But this inability to see others as real applies more generally to leftists and their supposed objects of concern. I was struck by this passage in The Liar (1991), an autobiographical novel by the near-ubiquitous British leftist Stephen Fry: “For Adrian other people did not exist except as bit-players in the film of his life. No-one but he had noted the splendour and agony of existence, no one else was truly or fully alive.” Fry is homosexual and half-Jewish, which may also be significant, but his solipsism is, I’d argue, an important feature of leftism. For leftists, collectivism is really the simplest and surest way to exalt the self. And you can see these aspects of leftism in the cult of Artemisia Gentileschi — and also in Gentileschi herself. Her bad art is now being worshipped in a major exhibition at the National Gallery in London. Here’s how Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett of the Guardian reacted when she overheard some truth-telling at the exhibition:

Artemisia’s features, in the guise of myriad saints and figures from myth and religion, are everywhere. As Laura Cumming wrote, she “seems to live inside every role she depicts”. I delighted in this, but other visitors did not. “Self-obsessed”, said one older man, and I laughed to myself because, really, his remark was just too perfect, too predictable, too tediously sexist for words. The history of women and art has been, in the main part, a history of bodies. Bodies stripped of clothing and imagined and objectified by men. Yet running alongside this parade of breasts and bottoms as conceived by the male gaze is a subversive counterhistory: that of women artists seeing themselves. (The history of art is full of female masters. It’s time they were taken seriously, The Guardian, Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett)

Yes, Gentileschi did see herself. She then put herself down on canvas, over and over again, in awkward, ugly, ill-coloured ways. That is subversive, I suppose. It’s definitely self-obsessed. Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett says the remark by the “older man” is “tediously sexist” because she can’t say that it’s untrue. Gentileschi also sometimes looks self-pitying, as in her Self-Portrait as Martyr, the painting on the left below:

Some of Artemisia’s subversive self-obsession: self-portraits as martyr, lute-player and St Catherine

Cosslett both explains and echoes the self-pity: “Artemisia was a survivor of male violence, just as I am. Tears sprang to my eyes when I looked at the transcript of her torture during her rapist’s trial, and read that she had repeated ‘è vero, è vero, è vero’ (‘it is true, it is true, it is true’).” I’d suggest that Cosslett wept for herself, not for Gentileschi. That is, Cosslett sees Gentileschi as a reflection of herself, not as an individual. That’s why objective standards of good and bad art don’t apply in the cult of Artemisia Gentileschi. She and her art serve to reflect feminists back at themselves.

And her art is probably even more appealing to feminists because, unlike Élisabeth Vigée-Le Brun’s, it is bad art. Leftists hate beauty, truth and goodness, and delight in the destruction of those things. The cult of Artemisia exalts ugliness and insists on untruths: Artemisia was a “genius,” a “uniquely gifted artist … among the all-time greatest painters.”

Chopping off White men’s heads

The cult also celebrates the overthrow of White men, because this is Gentileschi’s most famous painting in its two versions:

Judith Beheading Holofernes

Many painters have represented the ethnocentric Old Testament story of a Jewish heroine killing a gentile to defend her people, but few have done it as badly as Gentileschi did. And here is another of her bad paintings on a similar theme:

Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1615)

Gentileschi places herself on canvas, dealing death to White men, and feminists can again see themselves reflected in her bad art. If you want to see how a real genius represents Judith’s death-dealing, here is Caravaggio:

Caravaggio’s Judith beheading Holofernes (1599)

Compositionally, that isn’t one of Caravaggio’s best paintings: it isn’t a realistic portrayal of what such a beheading would have looked like (according to the apocryphal Book of Judith, Holofernes was drunk and helpless when Judith cut off his head as her maidservant kept watch at the door of his tent, but painters have understandably chosen more drama and less drunkenness). Gentileschi understood Judith’s task better, which is why she shows the beheading as a collaboration. After all, men are on average far more physically powerful than women, as Gentileschi presumably learned when she was raped by her father’s assistant, Agostino Tassi.

Victimhood valorizes

So yes, she was the victim of a bad crime and yes, the crime was compounded by the torture she endured to prove her accusation against Tassi. But her victimhood does not “valorize” her art (to use an ugly neologism found in this feminist art-criticism on Gentileschi). Her art is still bad and Caravaggio’s is still sublime. I’m not disturbed by Gentileschi’s decapitations. They might be more realistic, but they don’t look real. Caravaggio’s decapitation does look real.

And while Gentileschi painted herself as a martyr and saint, as you can see above, Caravaggio painted himself as a sinner, as you can see below:

Caravaggio’s The Taking of Christ (c. 1602)

The figure on the far left, holding up a lantern to assist the taking of Christ for trial and crucifixion, is probably Caravaggio himself. That is a very simple and effective way to represent a difficult but essential Christian doctrine: that we all bear responsibility for the crucifixion of God’s only-begotten son.

Anatomy out of whack

It’s also significant, I think, that Caravaggio has given a determinedly gentile face to the kiss-bestowing Judas, an archetypal Jewish villain in so much Christian iconography. There’s no evasion of responsibility here: Caravaggio is saying “I did it; you did it; we all did it.” But if Artemisia Gentileschi had attempted the same scene, I think her first impulse would have been to give Christ her own features and thereby play the victim again. She certainly couldn’t have painted to Caravaggio’s sublime standards. He could represent reality; she couldn’t. Even the Guardian and BBC acknowledge Gentileschi’s artistic failings:

Her anatomy is sometimes out of whack, her details occasionally glossed over (or perhaps painted by assistants). … the single light source in [Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (1623-5)] — a candle near Judith’s upper arm — is in the wrong place. It is too far behind Judith, who has her left hand held out catching the light that is clearly behind it, which is not possible. The mistake is compounded by a poorly painted shadow covering much of Judith’s face, which is also not possible. It’s a splodge and a botch. (Artemisia review — overwhelmingly present, The Guardian, 4th October 2020; Artemisia Gentileschi: Will Gompertz reviews her show at the National Gallery, BBC, 3rd October 2020)

Will Gompertz of the BBC then says: “And yet. Who cares?” I care and so should everyone who wants to defend artistic standards. Gentileschi’s failings aren’t minor and incidental, but major and characteristic. It matters that her “anatomy is sometimes out of whack” and that Caravaggio’s isn’t. She aimed for realism like him and didn’t achieve it. And without the example and inspiration of male painters like Caravaggio, she wouldn’t have reached even the low standards that she did. Whether feminists and other leftists like it or not, artistic genius and creativity are largely male things — more specifically, White male gentile things.

Some risibly bad art by Jean-Michel Basquiat

Feminists and other leftists don’t like it, of course, which is why they have created cults not just for Artemisia Gentileschi, but also for the risibly bad Black artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and the parodically minimalist Jewish artist Mark Rothko (see Brenton Sanderson’s three-part study of Rothko). Unlike them, Gentileschi valued realism, even if she didn’t achieve it. Basquiat and Rothko are part of what Tom Wolfe calls The Painted Word, that is, art that depends for its success not on its own merits, but on the spinning of verbal webs by disproportionately Jewish critics, academics and dealers. But Caravaggio’s realism — his ability to capture reality in paint — was not an isolated act of genius. It is no coincidence that his great art belongs to the same period as the birth of modern science and anatomy. Other White men were looking at the world and trying to understand and represent it in objective ways. Caravaggio was obsessed with light; Gentileschi was obsessed with herself.

The might of the “male gaze”

So are many of the feminists who now celebrate her and her subversive gynocentric reclamation of “breasts and bottoms as conceived by the male gaze,” as the Guardian journalist Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett put it. But if Cosslett wants true subversion, she should consider the fact that female breasts and bottoms were actually created by the male gaze. You could almost say that the human female is a work of art created by the human male, because countless acts of sexual selection down the course of evolution have favoured some types of women and disfavoured others. The sexual selection has worked in the other direction too, shaping male bodies according to female preferences.

But humans are not like Birds of Paradise, with drab, selective females and spectacular, attention-seeking males. The shaping of women by the “male gaze” may have been particularly strong in Europe when women were competing for the attention of skilled hunters in the colder and harsher European environment. The anthropologist Peter Frost argues that this female competition explains the variety of eye- and hair-colours found in Europe, where genes for blue eyes and blond hair appeared under pressure of the male gaze. In prehistoric times, White women were evolving special beauty even as White men were evolving special creativity.

Opposing beauty, pursuing power

In modern times, that White female beauty was celebrated by the art of White male creators. Later still, both the art and the beauty were attacked by leftist ideologies invented or decisively influenced by an alien group called Jews. I agree with a fascinating article at National Vanguard arguing that “Jews themselves are an unattractive and, on average, ugly people” and that “Jews, as a group, oppose beauty.” Indeed, the Talmud advises Jews not to regard physical beauty as important in marriage: “For ‘false is grace and beauty is vain.’ Pay regard to good breeding, for the object of marriage is to have children” (Taanith 26b and 31a).

The cult of Artemisia Gentileschi is a product of those leftist ideologies, celebrating a painter who was mediocre at her rarely achieved best. And just as Gentileschi’s art was not beautiful, nor was Gentileschi herself. She looks masculine and muscular, with high testosterone that may have given her the ambition and drive to promote herself in a way that her art could not do on its own merits. And she had novelty value as a female painter, of course. Cosslett says that a “large part of why Gentileschi captivates is because she triumphed against patriarchy.” But feminists like Cosslett don’t genuinely care about patriarchy or about rape. It wasn’t the Guardian or BBC that exposed the Muslim rape-gangs of Rotherham and numerous other British towns and cities. But it is the Guardian and BBC that support the continued growth in Western nations of Islam, which competes with Orthodox Judaism for the title of the world’s most patriarchal and misogynistic religion.

Instead, feminists like Cosslett care about themselves and about warring on truth, beauty and goodness. The cult of Artemisia Gentileschi is a small but characteristic battle-front in that war. Gentileschi was a bad artist who created ugly art. There are thousands of male artists far worthier of exhibitions at the National Gallery and of praise in the mainstream media. But those male artists don’t receive the attention they deserve. Not while leftism rules the media and inverts reality in its perpetual quest not for truth and beauty, but for power and revenge.